The toxin that causes botulism is the most potent that we know of - just 1/1,000th the weight of a grain of salt can be fatal, which is why so much effort has been put into keeping Clostridium botulinum, which produces the toxin, out of our food.

There are seven distinct, but similar, types of botulinum neurotoxin, produced by different strains of C. botulinum bacteria. Different sub-types of the neurotoxin appear to be associated with different strains of the bacteria. Genetic analysis of these genes will give us information about how they evolved.

The Institute of Food Research has been studying the bacteria and the way they survive, multiply and cause such harm. In new research, scientists have been mining the genome of C. botulinum to uncover new information about the toxin genes.

Dr. Andy Carter used data generated from sequencing efforts and compared the genome sequence of five different C. botulinum strains, all from the same group and all producing the same sub-type of neurotoxin.

An initial finding was that the five strains were remarkably similar in the area of the genome containing the neurotoxin gene. This suggests that the bacteria picked up the gene cluster in a single event, sometime in the past. Bacteria commonly acquire genes, or gene clusters, from other bacteria through this horizontal gene transfer. It is a way that bacteria have evolved to share 'weapons', such as antibiotic activity or the ability to produce toxins. To find out more about how C. botulinum acquired its own deadly weapon, researchers delved deeper into the genome sequence.

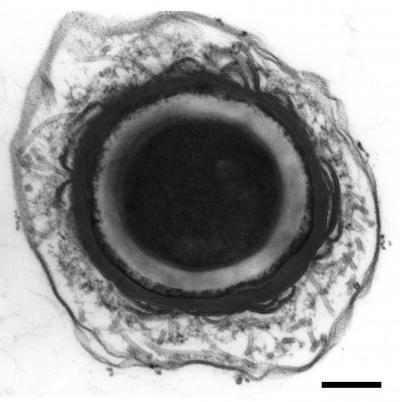

This is a spore of Clostridium botulinum. Credit: IFR

Like fossils of long lost organisms, they found evidence of two other genes for producing two of the other types of neurotoxin in the same region of the genome. Although these gene fragments are completely non-functional, finding them in the same place in the genome as the functional neurotoxin gene cluster is significant as it suggests that this region of the genome could be a 'hotspot' for gene transfer.

Looking to either side of the neurotoxin gene cluster uncovered more evidence supporting the hotspot idea. When the gene cluster inserted into the C. botulinum genome, it cut in two another gene. This gene is essential for the bacteria to replicate its DNA, so why does destroying it not prove fatal? C. botulinum was unaffected by this because contained in the segment of imported DNA was another version of the chopped-up gene.

Perhaps this is pointing us to the way C. botulinum first picks up its lethal weapon. This should help us prepare against the emergence of new strains, and may even one day help us disarm this deadly foe.

Comments