Panthera blytheae is the oldest big cat fossil ever found and fills a significant gap in the fossil record, according to results announced today.

The Panthera blytheae skull was excavated and described by a team led by Jack Tseng, a postdoctoral fellow at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York.

DNA evidence suggests that the so-called "big cats" – the Pantherinae subfamily, including lions, jaguars, tigers, leopards, snow leopards, and clouded leopards – diverged from their nearest evolutionary cousins, Felinae (which includes cougars, lynxes, and domestic cats), about 6.37 million years ago. However, the oldest fossils of big cats previously found are tooth fragments uncovered at Laetoli in Tanzania (the famed hominin site excavated by Mary Leakey in the 1970s), dating to just 3.6 million years ago.

Using magnetostratigraphy – dating fossils based on the distinctive patterns of reversals in the Earth's magnetic field, which are recorded in layers of rock – Tseng and his team were able to estimate the age of the skull at between 4.10 and 5.95 million years old.

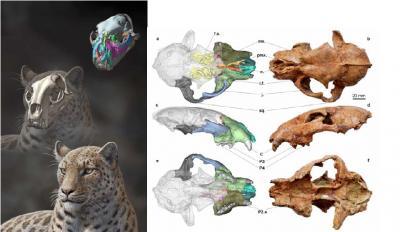

At left is: Life reconstruction of Panthera blytheae based on skull CT data; illustrated by Mauricio Antón. At Right are images of the holotype specimen and reconstructed facial bones based on CT data; Figure 1 from the paper. Credit: Mauricio Antón (left) and Figure 1 from the paper (right)

The new cat takes its name from Blythe, the snow-leopard-loving daughter of Paul and Heather Haaga, who are avid supporters of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

The find not only challenges previous suppositions about the evolution of big cats, it also helps place that evolution in a geographical context. The find occurs in a region that overlaps the majority of current big cat habitats, and suggests that the group evolved in central Asia and spread outward.

In addition, recent estimates suggested that the genus Panthera (lions, tigers, leopards, jaguars, and snow leopards) did not split from genus Neofelis (clouded leopards) until 3.72 million years ago – which the new find disproves.

Tseng, his wife Juan Liu, and Takeuchi discovered the skull in 2010 while scouting in the remote border region between Pakistan and China – an area that takes a bumpy seven-day car ride to reach from Beijing.

Liu found over one hundred bones that were likely deposited by a river eroding out of a cliff. There, below the antelope limbs and jaws, was the crushed – but largely complete – remains of the skull.

"It was just lodged in the middle of all that mess," Tseng said.

For the past three years, Tseng and his team have used both anatomical and DNA data to determine that the skull does, in fact, represent a new species.

They plan to return to the site where they found the skull in the summer to search for more specimens.

"We are in the business of discovery," said Wang, curator of vertebrate paleontology at the NHM; adjunct professor of geoscience and biology at USC; and research associate at AMNH. "We go out into the world in search of new fossils to illuminate the past."

Comments