Just as crocus and daffodil blossoms signal the start of a warmer season on land, a similar "greening" event--a massive bloom of microscopic plants, or phytoplankton--unfolds each spring in the North Atlantic Ocean from Bermuda to the Arctic.

Fertilized by nutrients that have built up during the winter, the cool waters of the North Atlantic come alive every spring and summer with a vivid display of color that stretches across hundreds and hundreds of miles. In what's known as the North Atlantic Bloom, millions of phytoplankton use sunlight and carbon dioxide (CO2) to grow and reproduce at the ocean's surface. During photosynthesis, phytoplankton remove carbon dioxide from seawater and release oxygen as a by-product. That allows the oceans to absorb additional carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. If there were fewer phytoplankton, atmospheric carbon dioxide would increase.

Flowers ultimately wither and fade, but what eventually happens to these tiny plants produced in the sea? When phytoplankton die, the carbon in their cells sinks to the deep ocean.

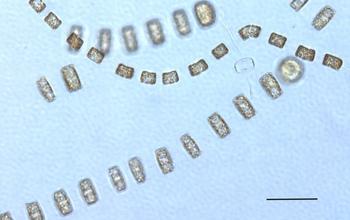

The chain-forming diatom Thalassiosira, seen under a microscope; it's a common bloom phytoplankton. Credit: Tatiana Rynearson

Plankton integral part of oceanic "biological pump"

This so-called biological pump makes the North Atlantic Ocean efficient at soaking up CO2 from the air.

"Much of this 'particulate organic carbon,' especially the larger, heavier particles, sinks," says scientist Melissa Omand of the University of Rhode Island, co-author of a paper on the North Atlantic Bloom published today in the journal Science.

"But we wanted to find out what's happening to the smaller, non-sinking phytoplankton cells from the bloom. Understanding the dynamics of the bloom and what happens to the carbon produced by it is important, especially for being able to predict how the oceans will affect atmospheric CO2 and ultimately climate."

In addition to Omand, other authors of the paper are Amala Mahadevan of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Eric D'Asaro and Craig Lee of the University of Washington, and Mary Jane Perry, Nathan Briggs and Ivona Cetiniæ of the University of Maine.

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF).

"It's been a challenge to estimate carbon export from the ocean's surface waters to its depths based on measurements of properties such as phytoplankton carbon," says David Garrison, program director in NSF's Division of Ocean Sciences. "This paper describes a mechanism for doing that."

Tracking a bloom: Floats, gliders and other instruments

During fieldwork from the research vessels Bjarni Saemundsson and Knorr, the scientists used a float to follow a patch of seawater off Iceland. They observed the progression of the bloom by taking measurements from multiple platforms.

Autonomous gliders outfitted with sensors were used to gather data such as temperature, salinity and information about the chemistry and biology of the bloom--oxygen, nitrate, chlorophyll and the optical signatures of the particulate matter.

At the onset of the bloom and over the next month, four teardrop-shaped seagliders gathered 774 profiles to depths of up to 1,000 meters (3,281 feet).

Analysis of the profiles showed that about 10 percent had unusually high concentrations of phytoplankton bloom properties, even in deep waters, as well as high oxygen concentrations usually found at the surface.

"These profiles were showing what we initially described as 'bumps' at depths much deeper than phytoplankton can grow," says Omand.

Staircases to the deep: Ocean eddies

Using information collected at sea by Perry, D'Asaro and Lee, Mahadevan modeled ocean currents and eddies ("whirlpools" within currents) and their effects on the spring bloom.

"What we were seeing was surface water, rich with phytoplankton carbon, being transported downward by currents on the edges of eddies," Mahadevan says.

"Eddies hadn't been thought of as a major way organic matter is moved into the deeper ocean. But this type of eddy-driven 'subduction' could account for a significant downward movement of phytoplankton from the bloom."

In related work published in Science in 2012, the researchers found that eddies act as early triggers of the North Atlantic Bloom.

Eddies help keep phytoplankton in shallower water where they can be exposed to sunlight to fuel photosynthesis and growth.

Next, the scientists hope to quantify the transport of organic matter from the ocean's surface to its depths in regions beyond the North Atlantic and at other times of year and relate that to phytoplankton productivity.

Learning more about eddies and their link with plankton blooms will allow for more accurate global models of the ocean's carbon cycle, the researchers say, and improve the models' predictive capabilities.

Comments