Of the uncertainties facing climate modelers, climate feedbacks from decomposition by soil microbes are among the biggest.

The dynamics among soil microbes allow them to work more efficiently and flexibly as they break down organic matter – spewing less carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than previously thought, according to a new study from the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) and the University of Vienna published in Ecology Letters.

"Previous climate models had simply looked at soil microbes as a black box," says Christina Kaiser, lead author of the study who conducted the work as a post-doctoral researcher at IIASA. Kaiser, now an assistant professor at the University of Vienna, developed an innovative model that helps bring these microbial processes to light.

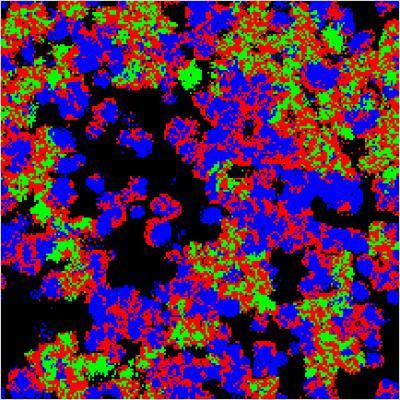

This is a visual representation of the model output. Credit: Christina Kaiser: IIASA/University of Vienna

Microbes and the climate

"Soil microbes are responsible for one of the largest carbon dioxide emissions on the planet, about six times higher than from fossil fuel burning," says IIASA researcher Oskar Franklin, one of the study co-authors. These microbes release greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere as they decompose organic matter. At the same time, the Earth's trees and other plants remove about the same amount of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through photosynthesis.

As long as these two fluxes remain balanced, everything is fine.

But as the temperature warms, soil conditions change and decomposition may change. And previous models of soil decomposition suggest that nutrient imbalances such as nitrogen deficiency would lead to increased carbon emissions. "This is such a big flux that even small changes could have a large effect," says Kaiser. "The potential feedback effects are considerably high and difficult to predict."

Diversity does the trick

How exactly microorganisms in the soil and litter react to changing conditions, however, remains unclear. One reason is that soil microbes live in diverse, complex communities, where they interact with each other and rely on one another for breaking down organic matter.

"One microbe species by itself might not be able to break down a complex substrate like a dead leaf," says Kaiser. "How this system reacts to changes in the environment doesn't depend just on the individual microbes, but rather on the changes to the numbers and interactions of microbe species within the soil community."

To understand these community processes, Kaiser and colleagues developed a computer model that can simulate complex soil dynamics. The model simulates the interactions between 10,000 individual microbes within a 1mm by 1mm square. It shows how nutrients, which influence microbial metabolism, affect these interactions, and change the soil community and thereby the decomposition process.

Previous models had viewed soil decomposition as a single process, and assumed that nutrient imbalances would lead to less efficient decomposition and hence greater greenhouse gas emissions. But the new study shows that, in fact, microbial communities reorganize themselves and continue operating efficiently – emitting far less carbon dioxide than previously predicted.

"Our analyses highlight how the systems thinking for which IIASA is renowned advances insights into key ecosystem services," says study co-author and IIASA ecologist Ulf Dieckmann.

"This model is a huge step forward in our understanding of microbial decomposition, and provides us with a much clearer picture of the soil system," says University of Vienna ecologist Andreas Richter, another study co-author.

Comments