In America it seems that Democrats are gaining ground and that therefore the culture is moving to the left. It's actually much different, Democrats have actually moved to the right. President Obama came into office campaigning against two wars but will leave office with three. He never closed Guantanamo Bay and even his lifting of "the ban" on human embryonic stem cell research was just a slight modification of the NIH funding policy under President George W. Bush.

At the Democratic National Convention, President Obama announced the death of Osama Bin Laden at the hands of U.S. special operations forces to a standing ovation, hardly the Democrats of the previous 30 years. Health care and energy initiatives promoted by the administration have been very pro-corporation.

In the United Kingdom, the situation is much different; the center has gone so far left that if the left is not left enough, voters will penalize politicians by voting for the right. Even the right is more left than perception, according to a new paper from the University of Sussex and Queen Mary University of London.

A study into the views of supporters of the main political parties in the country suggests that many are more left wing than they think they are.

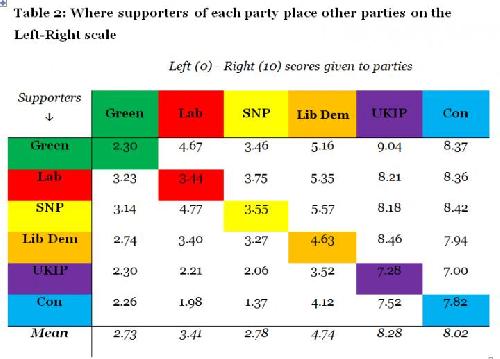

The researchers asked enthusiastic supporters of the Conservatives, Greens, Labour, Liberal Democrats, SNP and UKIP to place themselves, the party they support, and the other five parties on an ideological scale from zero (very left-wing) to 10 (very right-wing).

They then asked them some direct, ideologically-charged questions in order to build up a picture of their underlying political attitudes.

The results, published online, show a mismatch between these arguably more objective measures and the subjective answers given by the participants.

For example, diehard Conservative supporters locate their party at 7.82 on the left-right spectrum (ie considerably right of centre) and place themselves at 7.53. But the more 'objective' measure suggests their political leanings are only just right of centre, producing a score of 5.08.

The pattern is consistent across the six parties, with UKIP providing the most striking example. UKIP supporters see themselves as closer to the centre ground (6.77) than their party as a whole (7.28), while the researchers measured them as being considerably left of centre (2.62).

The researchers do strike a note of caution, however, in drawing too many firm conclusions.

Professor Paul Webb, Professor of Politics at the University of Sussex, said: "While our findings appear to show that we may be a more left-wing bunch than we commonly perceive, some of this could be down to the questions we asked to obtain our 'objective' score.

"Although we used a standard measure, it only satisfactorily taps into the economic rather than the social dimension of political ideology."

Nevertheless, the 'subjective' part of the study provides some interesting findings of its own.

For example, in the majority of cases, the parties' strongest supporters see themselves not as more radical or extreme than the parties they support but as more centrist. The clear exception is for Labour, whose supporters - polled before last summer's leadership election - saw themselves as considerably more left-wing than the party as a whole, which may help to explain Jeremy Corbyn's 'surprise' election as leader.

Unsurprisingly, supporters of the country's two biggest parties see their opposing parties as more left-wing (in the case of Labour) and more right-wing (Conservatives) than do the parties' own supporters.

Professor Webb added: "Political commentators often refer to winning the battle for the centre ground as the holy grail for election campaigns, but our study shows just how difficult it is to determine exactly where this is and what it looks like. Perhaps that is why, for so many politicians, it proves so elusive."

The researchers surveyed a cross-section of voters who declared a strong allegiance to one political party. While the number of people in this camp has shrunk over the last half century, they still represent an estimated 15 per cent of the electorate (around seven million people).

The surveys were carried out in the wake of the 2015 General Election as part of a wider ESRC-funded project on party membership in the 21st century.

Comments