The advantage of using two eyes to see the world around us has long been associated solely with our capacity to see in 3-D. Now, a new study from a scientist at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute has uncovered a truly eye-opening advantage to binocular vision: our ability to see through things.

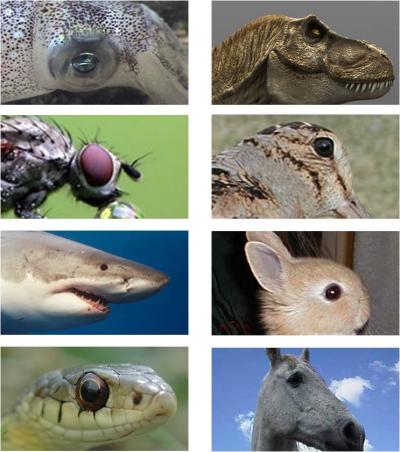

Most animals — fish, insects, reptiles, birds, rabbits, and horses, for example — exist in non-cluttered environments like fields or plains, and they have eyes located on either side of their head. These sideways-facing eyes allow an animal to see in front of and behind itself, an ability also known as panoramic vision.

Humans and other large mammals — primates and large carnivores like tigers, for example — exist in cluttered environments like forests or jungles, and their eyes have evolved to point in the same direction. While animals with forward-facing eyes lose the ability to see what's behind them, they gain 'X-ray vision', according to Mark Changizi, assistant professor of cognitive science at Rensselaer, who says eyes facing the same direction have been selected for maximizing our ability to see in leafy environments like forests.

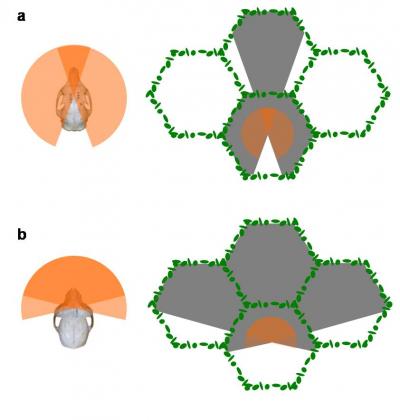

All animals have a binocular region — parts of the world that both eyes can see simultaneously — which allows for what he calls X-ray vision and grows as eyes become more forward facing.

Demonstrating our 'X-ray' ability is fairly simple: hold a pen vertically and look at something far beyond it. If you first close one eye, and then the other, you'll see that in each case the pen blocks your view. If you open both eyes, however, you can see through the pen to the world behind it.

To demonstrate how our eyes allow us to see through clutter, hold up all of your fingers in random directions, and note how much of the world you can see beyond them when only one eye is open compared to both. You miss out on a lot with only one eye open, but can see nearly everything behind the clutter with both.

"Our binocular region is a kind of 'spotlight' shining through the clutter, allowing us to visually sweep out a cluttered region to recognize the objects beyond it," says Changizi, who is principal investigator on the project. "As long as the separation between our eyes is wider than the width of the objects causing clutter — as is the case with our fingers, or would be the case with the leaves in the forest — then we can tend to see through it."

To identify which animals have this impressive power, Changizi studied 319 species across 17 mammalian orders and discovered that eye position depends on two variables: the clutter, or lack thereof in an animal's environment, and the animal's body size relative to the objects creating the clutter.

Changizi discovered that animals in non-cluttered environments — which he described as either "non-leafy surroundings, or surroundings where the cluttering objects are bigger in size than the separation between the animal's eyes" (think a tiny mouse trying to see through 6-inch wide leaves in the forest) — tended to have sideways-facing eyes.

"Animals outside of leafy environments do not have to deal with clutter no matter how big or small they are, so there is never any X-ray advantage to forward-facing eyes for them," says Changizi. "Because binocular vision does not help them see any better than monocular vision, they are able to survey a much greater region with sideways-facing eyes."

However, in cluttered environments — which Changizi defined as leafy surroundings where the cluttering objects are smaller than the separation between an animal's eyes — animals tend to have a wide field of binocular vision, and thus forward-facing eyes, in order to see past leaf walls.

"This X-ray vision makes it possible for animals with forward-facing eyes to visually survey a much greater region around themselves than sideways-facing eyes would allow," says Changizi. "Additionally, the larger the animal in a cluttered environment, the more forward facing its eyes will be to allow for the greatest X-ray vision possible, in order to aid in hunting, running from predators, and maneuvering through dense forest or jungle."

Changizi says human eyes have evolved to be forward facing, but that we now live in a non-cluttered environment where we might actually benefit more from sideways-facing eyes.

"In today's world, humans have more in common visually with tiny mice in a forest than with a large animal in the jungle. We aren't faced with a great deal of small clutter, and the things that do clutter our visual field — cars and skyscrapers — are much wider than the separation between our eyes, so we can't use our X-ray power to see through them," Changizi says. "If we froze ourselves today and woke up a million years from now, it's possible that it might be difficult for us to look the new human population in the eyes, because by then they might be facing sideways."

Changizi's research was completed in collaboration with Shinsuke Shimojo at the California Institute of Technology, and is published online in the Journal of Theoretical Biology. It was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Changizi's 'X-ray vision' research, along with his research about our 'future-seeing powers', 'color telepathy', and eye computation abilities, will appear in his book The Vision Revolution, due out in stores this spring.

Comments