Retinitis pigmentosa is an incurable and unpreventable blinding eye disease that affects 1 in 4,000 people but if "in mice" isn't caution enough, even more is warranted. Other studies have found that the complement system worsens retinal degeneration because it mediates some aspects of inflammation and worsens damage in age-related macular degeneration (AMD), a leading cause of blindness in people age 65 years and older.

The team monitored the genetic expression of the complement system in a transgenic mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa. They found that upregulation of complement expression and activation coincided with the onset of photoreceptor degeneration. What's more, this upregulation occurs in the exact location of the degeneration. With complement evident, they wanted to know whether it was helping or hurting the degenerative process.

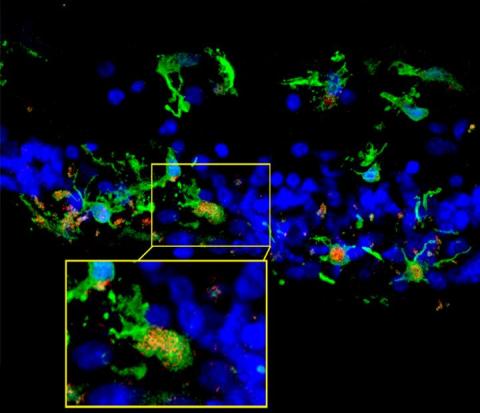

Retinal sections are shown from a patient with retinitis pigmentosa. Within the degenerating photoreceptor layer (blue), multiple microglia (green) are observed. Image: Wai Wong, M.D., Ph.D., National Eye Institute.

Using the retinitis pigmentosa mouse model, the researchers examined the role of C3 and CR3, the central component of complement and its receptor, by comparing mice with genetically ablated C3 or CR3 to mice with normal expression. They found that the absence of C3 or CR3 made degeneration worse. Rod photoreceptors, the light-sensing cells that die off first in retinitis pigmentosa, were precipitously lost along with a surge in the expression of neurotoxic inflammatory cytokines.

They pieced together that C3 gets secreted by microglia, trash-collecting cells that in a healthy retina clear away dead cells by phagocytosis to keep the tissue working properly. Once secreted, C3 lands on dead photoreceptors labeling them for destruction and removal. The receptor, CR3, recognizes the C3 markers and conveys the information to microglia. Breakdown of this C3-CR3 interaction resulted in a decreased ability of microglia to phagocytose dead photoreceptors, which then accumulate in the retina, stimulating greater inflammation and degeneration. Degeneration accelerates pretty quickly, they said.

When placed alongside each other in a dish, microglia from C3- or CR3-ablated retinas turned out to be toxic to photoreceptors. Taken together, the results show that in the context of retinitis pigmentosa, complement activation is actually helpful for clearing away dead cells and maintaining a state of homeostasis, a physiological balance, in the retina.

Comments