With all of those challenges, Martian landers have still been able capture wind measurements — some gauging the cooling rate of heated materials when winds blow over them, others using cameras to image “tell-tales” that blow in the wind. Both anemometric methods have yielded valuable insight into the planet’s climate and atmosphere.

If humans ever intend to go there, we'll need more data first.

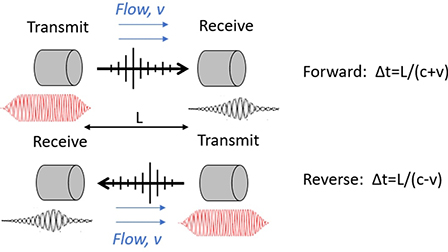

A recent paper demonstrated a sonic anemometric system featuring a pair of narrowband piezoelectric transducers to measure the travel time of sound pulses through Martian air. The study accounted for variables including transducer diffraction effects and wind direction.

“By measuring sound travel time differences both forward and backward, we can accurately measure wind in three dimensions,” said author Robert White. “The two major advantages of this method are that it’s fast and it works well at low speeds.”

The researchers hope to be able to measure up to 100 wind speeds per second and at speeds as low as 1 cm/s, a remarkable contrast to previous methods that could register only about 1 wind speed per second and struggled to track speeds below 50 cm/s.

“By measuring quickly and accurately, we hope to be able to measure not only mean winds, but also turbulence and fluctuating winds,” said White. “This is important for understanding atmospheric variables that could be problematic for small vehicles such as the Ingenuity helicopter that flew on Mars recently.”

The researchers characterized ultrasonic transducers and sensors over a wide range of temperatures and a narrow range of pressures in carbon dioxide, the primary atmospheric gas on Mars. With their selections, they showed only nominal error rates would result from temperature and pressure changes.

“The system we’re developing will be 10 times faster and 10 times more accurate than anything previously used,” said White. “We hope it will produce more valuable data as future missions to Mars are considered and provide useful information on the Martian climate, perhaps also with implications for better understanding the climate of our own planet.”

Comments