This week I am spending my evenings in the CDF control room, as a Scientific Coordinator. That literally means being in control of what happens to the detector and its subsystems, and ensuring that data is collected with the maximum efficiency. Of particular concern are situations when there are warnings or other alarms from a subsystem which is deemed "critical" for the flagging of data as "good for physics". In such circumstances, we need to take prompt action, trying to figure what the problem is, and if needed call the relevant expert. There are at least three dozen page carriers in the area around Fermilab, who are instructed to run to the aid of their subsystem, in case something odd happens. And the CDF electronic logbook is read daily by a hundred more of our collaborators, who care for their detector and the data we collect.

The shift crew is composed of a Scientific Coordinator (SciCo), plus an Ace -the person who actually executes all computer commands to control the systems and the data taking- and a Consumer Operator -the person who controls the quality of the data being collected, by comparing running histograms with reference ones. The SciCo mostly sits and watches, in the middle of the big control room, and supervises the proceedings. He or she is the one who sometimes has to take decisions on how to react to emergencies. Among the duties there is the supervision of data taking, the responsibility for enforcing the emergency response procedures (say in case of fire, or oxygen deficiency alarms), the care of voltages and currents of our silicon detector, the communications with the main control room and with experts, and a very particular procedure to perform only when the silicon, our most precious subsystem, is in danger of being burnt by a malfunction in its cooling system.

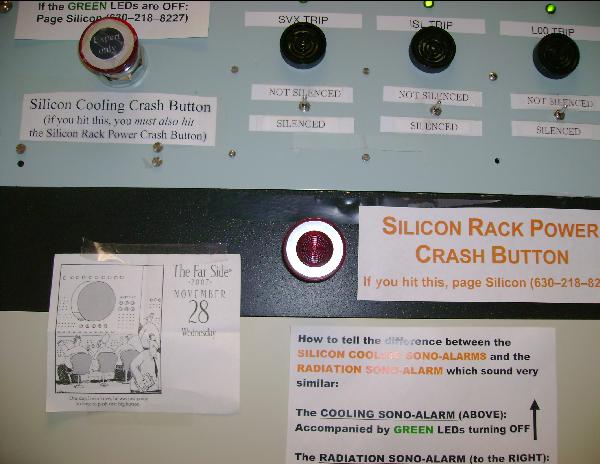

I have not visited too many control rooms of complex experiments or systems in my life, but I bet that most of them are instrumented with something resembling the thing seen below, a "big red button": something to push when s**t happens.

Gary Larson even made a cartoon about it (you can see it on the left), and as always his humour is spot-on: in every control room, there is somebody who is constantly thinking at the chance that he or she will one day have to hit the big button! The legend says "One day, Irwin knew, he was just going to have to push that big button". Consequences are dire: once you press the button, you will be called to explain why you did. And if you do not push it in case it is needed, responsibilities are even heavier.

Today things are running smoothly in the control room. But yesterday, if we speak of loss of control... Well: at a certain point, at least four subsystems decided to give warnings or alarms: the silicon, the XFT, the Level 3, the data quality monitoring system. It must have been funny watching us frantically going from one terminal screen to another, issuing computer commands, calling people over the phone, answering other calls and keeping people on hold. Fortunately, these activities are short-lived, else I would not stand the stress.

So here I am pictured after the smoke cleared, toward the end of my shift yesterday: as you see, I do not look stressed at all. Bored, maybe.

Comments