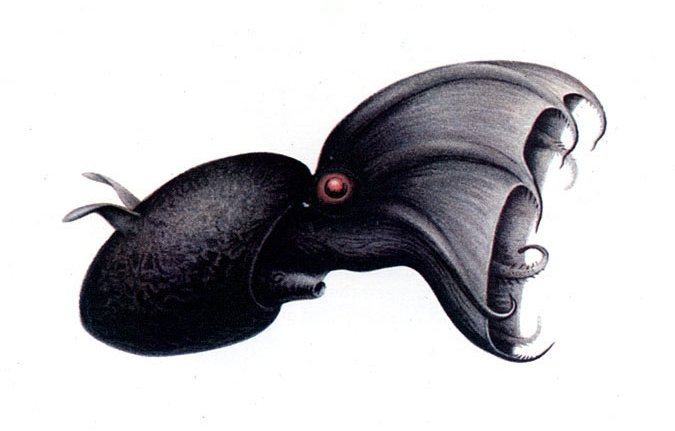

Everyone loves vampire squid, right? Their monstrous name belies their gentle nature as graceful underwater flyers who eat poop.

Still, I was surprised--and delighted!--when a new study about the sex lives of vampire squid made national and international headlines. Well, okay, when I phrase it like that the appeal is pretty obvious. But what was the actual news, you ask--what did the study find?

Vampire squid are the first coleoid cephalopod to demonstrate true iteroparity.

Aren't you just so excited now? No? Let me tell you why you should be.

All the squid and octopuses and cuttlefish that have been studied up until now enter a "reproductive phase" at the end of their lives. Females, in particular, begin to devote all their energy to ripening and spawning eggs. There are extremes, from the octopus mothers who starve to death while guarding their eggs to the squid mothers who keep on merrily eating and growing while popping out mass after mass of eggs. But in all cases, the beginning of spawning is the beginning of the end of life.

Not so in vampire squid. As published in the journal Current Biology, biologist Henk-Jan Hoving and his colleagues found that female vampire squid actually go through a "resting phase" between spawning events. Their ovaries take a break and they go back to a carefree bachelorette existence. This is called iteroparity and it's pretty amazing because it's so completely different from what every other cephalopod does.

Well. Not every other cephalopod.

Yes, all the other squid and octopuses and cuttlefish are big blow-out spawners. But they're not the only cephalopods. Nautiluses, with their heavy external shells and upwards of 60 tentacles, are more distant cousins, but they are cephalopods. In fact, they're the originals. The six species of nautilus alive today are remnants of an ancient group that was once far more diverse and abundant.

Yes, all the other squid and octopuses and cuttlefish are big blow-out spawners. But they're not the only cephalopods. Nautiluses, with their heavy external shells and upwards of 60 tentacles, are more distant cousins, but they are cephalopods. In fact, they're the originals. The six species of nautilus alive today are remnants of an ancient group that was once far more diverse and abundant.And before Hoving's study, nautiluses were the only known iteroparous cephalopods.

Paleontologists think that nautiluses and their ancestors have been following this reproductive strategy for a long time. It may have both hindered and helped them. Slow, spaced-out spawning could have contributed to the group's decline, but it may also have pulled them through the mass extinction that ended many other groups of fossil cephalopods (oh yeah, and dinosaurs).

Vampire squid have followed a surprisingly similar evolutionary trajectory. Many different kinds swam in the Jurassic seas, but, for unknown reasons, only a single species survived to modern times. Also unknown is whether vampire squid developed their iteroparous spawning strategy recently, or if, like nautiluses, they've been doing it for a hundred million years.

If iteroparity was indeed an ancient vampire squid practice, I can't help but wonder if the theories about nautilus decline and survival could apply to vampires as well. In any case, I hope the vampire squid's sex life will eventually enhance our evolutionary view of cephalopods, as well as contributing to our knowledge of their habits today.

Images: Vampyroteuthis drawing by Chun. (Public domain)

Nautilus in Palau by Manuae. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Fossil vampire squid by Willsquish. (Public domain)

Comments