Rogue wheat is growing in wheat fields in 127 countries around the world! Should consumers be concerned?

Ok, I'm indulging in a poor imitation of the emotive language common in sensational writings about food issues. What I said in the paragraph above is all true, it's just misleading because of a lack of context. After the "crisis" of glyphosate tolerant wheat being found in an Oregon field, I thought it would be useful to put that event into perspective. So...

Wheat 1.0

Wheat is largely a "saved seed crop," meaning that farmers set aside some of the grain from each harvest to use as seed the next year. This is a practical thing for these growers to do because planting rates of wheat seed are very high (e.g. 80 or more lbs/acre) so it would be very expensive to haul bags or bins of seed very far. Also, except for a little bit in Europe, wheat is not a hybrid crop, like corn, so it is not necessary to buy new seed each year to get the highest yielding types. If a farmer plants the wheat from last year's crop, he/she will get the same kind of wheat in the new harvest... well, mostly. Wheat is not pollinated by insects, but rather by wind, so pollen can blow in from another field where the variety might be different. This is something like a 1% issue. The wheat can get mixed over time because of little amounts left in combines or grain wagons. Also, weed seeds can build up over time - that is definitely rogue genetics! Over time, if only saved seed is used, the field will represent a mix of genetics.

This "genetic drift" is problematic for wheat producers, because unlike some other major crops, there are extremely important quality differences between types of wheat. These differences are related to genetics, and the price a farmer can get for the crop often depends on being able to achieve certain standards. There are specialists within the field of food science called "Cereal Chemists" who measure all sorts of properties of wheat to characterize lots of wheat/flour so that bakers and others can get the results they desire. (When I first heard the term cereal chemist I thought they were saying "serial chemist:" e.g. someone who keeps committing chemistry!)

Wheat is Not Just Wheat

Wheat is definitely not just one commodity. There are very different wheats that have been bred over the centuries for very different purposes. The major categories of wheat are "Hard" or "Soft," "Red" or "White," "Winter" or "Summer," and "Normal" vs "Durum." So for baking an artisan bread or making pizza crust where "dough strength" is important you want a "Hard Red Spring Wheat." If you want to make Asian soft noodles you want a "Soft White Spring Wheat." If you want to make pasta, you want "Spring Durum Wheat."

The various types of wheat achieve their best quality in different geographic/climatic regions, but even within a region and a type of wheat, there are differences in quality based on the variety and the weather in a given growing season. If you are a wheat farmer growing for any of those (or many other) specific markets, you have to be concerned about the purity of the genetics of the wheat in your field. If you plant a high quality variety for a specific use, you can only replant with saved seed for a few years before genetic and/or variety drift - "rogue genetics" if you will - renders your crop of too poor quality for your market.

How The Wheat Industry Manages This Issue

This issue of genetics has been a very long-term challenge for wheat growers. Long ago, the industry set up a system to deal with it. Crop Improvement Associations were established in each state to oversee the careful production of specific varieties with enough isolation from other fields of wheat and with inspection to insure that the resulting "certified seed" is genetically pure enough. In fact, there is a specialized verb, roguing, which refers to eliminating the genetic off-types in a seed field. This is just part of how real seed production is done.

Certain farmers in every geography specialize in growing this seed, and they then sell it to their neighbors with a small premium above commodity grain prices to pay for the effort and the testing. Because of this system, wheat growers can deliver wheat with specific quality requirements in spite of the unavoidable genetic drift in their fields. If the quality requirements are super exacting (e.g. those who grow the varieties for Wheaties and other branded, specialty wheat products), it is often grown under a contract which requires that new certified seed is used for every planting. Unlike corn and soy where the harvest is typically commingled in one big, efficient "river" of grain, for wheat, lot-by-lot "identity preservation" is common. Reliably delivering specific types of wheat to different customers is completely feasible.

The 2002 Intimidation of the North American Wheat Industry Didn't Have To Go Down Like That

As I've described in a previous post, GMO wheat was on the verge of commercialization around 2002 when European and Japanese buyers threatened to boycott all North American wheat if any commercial GMO wheat was planted. Threatened with the loss of lucrative markets, the US and Canadian growers reluctantly asked Syngenta and Monsanto to halt their commercialization plans. What is sad is that standard certified seed and identity preservation mechanisms could have been employed to allow North American wheat growers to both enjoy the benefits of plant biotechnology and still meet the non-GMO demands of some of their customers. All that would have been needed was a rational threshold for "adventitious presence" of tiny amounts of other genetics - something that is already commonplace for "rogue" genetics of other types. When European millers buy Hard Red Spring Wheat from Canada or North Dakota, there are defined standards for how much of something else could be present because of carry-over from bins or harvesting equipment, etc. In the grain industry it is not normal to have a zero tolerance - that just isn't practical. The same should have been the case for non-GMO wheat.

The current "rogue GMO wheat" debacle in the Pacific North West never needed to happen. All the regulatory approvals were on track to be granted and sizable field trials had been conducted. Efforts were certainly made to prevent any gene flow from the tests to other wheat, but it would not have been some disaster if it had happened. Again, the system was in place to manage that genetic issue just like every other one in this complex crop. Instead, the entire process was derailed setting things up for this "crisis" in Oregon today. It will only be a crisis if the Asian customers respond irrationally. Unfortunately, this is what they seem to be doing.

So yes, there is "rogue wheat" in fields in 127 countries. Using time-tested protocols we can still have wheat that is genetically pure enough to make all the delicious foods we make from different kinds of wheat. What happened in Oregon need not disrupt that if the customers will allow the industry to deal with it the way they deal with all genetic drift issues.

You are welcome to comment here and/or to email me at savage.sd@gmail.com

#GMOReason #wheat @grapedoc

Photo of "Palouse Wheat Field Sunrise" from the Charles Knowles Gallery

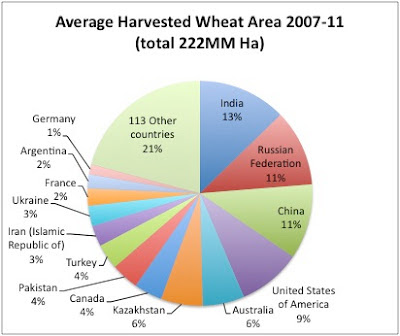

I can't resist putting some data in a post, so here is a graph of world wheat planting based on FAOSTATS

Comments