Though 16th century peasants during the time of Paracelsus readily understood that 'the dose makes the poison', our own National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS, who funded the new study in question) instead routinely claims that 'any pathogen is pathology' - that is to say that any trace of any chemical that may be a hazard is dangerous and needs to be in their in-house anti-science fanzine, Environmental Health Perspectives, so it can be promoted by the New York Times.

'Risk' in papers is population level so it is categorized as "exploratory." There are different kinds of risk, absolute and relative. If your chance of dying due to chemical X is 1 in a billion, that is low relative risk, but if the risk might be 2 in a billion due to other factors, and a headline screams '100% increased risk!' that sounds scary, unless you recognize your relative risk might not have changed at all.(1)

A new paper claiming they can link a common pesticide class, called Pyrethroids, to increased mortality follows this playbook exactly:

Source: Matthew Hankins

An "exploratory" paper is the scientific equivalent of 'that's interesting, maybe we should look at it' but in the hands of university public relations writers and sympathetic journalists who grew up being told by their elders in their occupation to distrust food, medicine, and chemistry, surrounding a statistical correlation with words like "suggests" and terms like "has been linked to" is going to get coverage. Journalists often do not know that rats are not little people, an animal study cannot show human benefit or harm, they can only invalidate them because of the narrow biology similarities. That is why no drug can be approved based on mice studies, they have to do human clinical trials. Yet when it comes to mouse models showing harm, journalists are happy to help scare the public invoking human risk that may not exist.

We can't always do human clinical trials, of course. To discover that smoking, smog (the real kind, PM10, not the "virtual" smog PM2.5 kind), and alcohol were truly carcinogenic, there were not controlled human experiments, that would be unethical. Those were instead home runs for epidemiology, the original International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), led by the legendary Dr. John Higginson, used rigorous methods to create a true "weight of evidence" (much different than the quasi-fraudulent "emerging" evidence, which could mean one paper) and make the case against those. But two generations later IARC became overrun with activists consulting for environmental groups and even signing contracts with trial lawyers to sue over products under review even before IARC declared them hazardous.

A surge of people went into epidemiology after the success against smoking, but a whole lot of people chasing a finite pool of money led to desperation. And that led to the kind of media 'clickbait' claims using "has been linked to" and "suggests" using survey results we see every week now. Everyone wants to claim to find the new smoking, and get famous campaigning against a new Big Tobacco, but it doesn't exist in either case.

That's the reason why it is now common to see a new paper, an observational claim (thus the fuzzy-wuzzy "exploratory" qualifier) used a tiny 2,116 adults from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (a survey, so prone to recall bias, another confounder) to claim that common Pyrethroid insecticides mean a higher "risk" of death over about 14 years.(2) 90 people died when it should have only been 75 and the only thing they could fathom as the cause was the pesticide.

But they didn't measure any pesticides, they used a proxy; a 3-phenoxybenzoic acid biomarker, a metabolyte in urine samples. Chemists, biologists, and toxicologists will tell you two things about this paper and its glaring flaw before they even read it: we can detect anything in anything in 2019, and if it's in urine samples then the body is working. It's detecting it in blood or tissues that would be a concern at high enough levels. They spin the "prospective" nature of their methodology into a positive, claiming the pesticide exposure may be even greater than they estimate because these were spot urine tests. Without mentioning that means it could also be far lower.

Experts in statistics will tell epidemiologists one more important thing:

Epidemiologists try to be jacks-of-all-trades in many fields, but many are experts in none, so there is a strong chance they either got the methodology 'wrong' or their implicit bias got in the way. Let's face it, if you got a grant to show White Zinfandel causes cancer, you are really going to look for White Zinfandel causing cancer, and therefore you are far more likely to find it in the data.(3)I'm a statistician. My motto is 'I haven't read your paper yet but I'm virtually certain your methods are flawed&your results are wrong.'

— Stephen John Senn (@stephensenn) April 9, 2014

Timber logging and being an Alaskan crab fisherman both have a statistically higher risk of death over 14 years but that does not mean your wood floors or a crab puff are unsafe, yet that is the reasoning it takes to believe a common pesticide that is in use far below No Effect Levels is killing farmers. It requires ignoring a lot of confounders.

The problem with the claim in the new paper is obvious to epidemiologists who are more neutral; agriculture is hard work, it is often done by poor people, and socioeconomics are a far greater health factor than a proxy that can be linked to a common pesticide.

But JAMA has to share some of the blame for scaremongering because they hand-picked editorial writers from Columbia, fellow epidemiologists even, at a $55,000 per year school in Manhattan without a single agriculture employee, to take this exploratory result, statistical wobble that ignores numerous confounders, and turn it into a call for action.

That is exactly what erodes public confidence in science.

There is a movement among the science community to stop the statistical significance fetish, especially by epidemiologists, and the reasons to do so are solid. It is abusing the public's confidence in all science. Why should the public trust scientists on global warming if a drop of a pesticide in 60 Olympic-sized swimming pools can be "linked" to deaths or endocrine disruption or whatever other reformulated homeopathy is passing for consumer advocacy among the epidemiology community? In greenhouses, plants grow better with more CO2, after all. That is the same logic epidemiologists and activists use when claiming some chemical or food needs to be banned based on either suspicious proxies or lethal doses in animals.

You can be certain organic food industry trade groups will promote this, but as a reader, you should be more skeptical that a common pesticide used for decades is suddenly killing farm workers. And if you are a scientist, you should criticize the paper the way you would any easy targets, like vaccine deniers.

NOTES:

(1) Use some judgment. There are cases where your relative risk is instead really high, it just isn't if you are a farmworker using a pesticide that is safe.

Credit: Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal by Zach Weinersmith.

(2) "Risk" always sounds scary. IARC, for example, throws around the term "risk" in their media kits when they are trolling for attention but they don't do risk at all, they only do "hazard", so to create a hazard they will allow 5 orders of magnitude. To them, one dose is the same as 10,000 doses. Like I wrote above, 16th century peasants knew that one drink of whisky was not the same as 10,000, or even water for that matter. That is why IARC laughingly has bacon as the same carcinogen level as plutonium and mustard gas. They are right, all of them can kill you, but a tiny bit of mustard gas or plutonium will while it's unrealistic for a human to eat enough bacon.

So if you never eat bacon you have a 5% chance of getting colon cancer, whereas if you eat 10,000 bacon sandwiches you may have a 6% chance of getting colon cancer.

What is the crossover between none and 10,000? Epidemiologists have no idea but they still claim bacon is just like smoking or high doses of radiation.

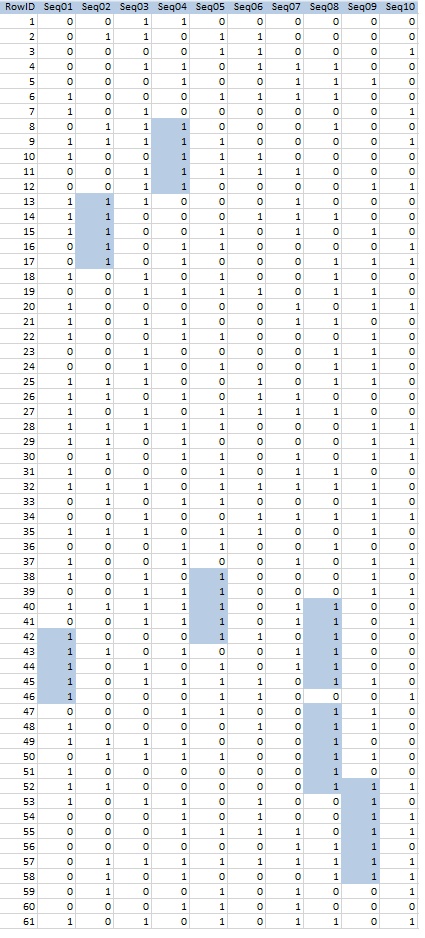

(3) If you got that grant to show that coin flips are not random, they are correlated to tails, you can find that also. Just find enough "clusters" of tails to claim statistical significance. Harvard made this technique popular in the 1980s when they did it with Food Frequency Questionnaires in the 1980s. If you are now fatigued by weekly 'food Z makes you healthy' and 'chemical Y linked to death' claims in corporate journalism, thank the Harvard School of Public Health.

It is easier than you think, literally using the technique popularized by Harvard:

61 rows, coin flips here but for Harvard School of Public Health they are foods, and 10 columns, which to them are health effects. Using a coin flip random generator, if seven times out of 10 you get runs of five tails in a row, you can claim that coin flips are not random with statistical significance, even though each.

Now it is more than just food. Epidemiologists use this same method, gather a lot of data, hand-select the thing you want, to claim the election of President Trump caused Latina women to go into pre-term labor, but it was only 0.00007 more.

Source: Drs. Stan Young and Henry Miller, Genetic Literacy Project.

Comments