Melville on Science vs. Creation Myth

Melville on Science vs. Creation MythFrom Melville's under-appreciated Mardi: On a quest for his missing love Yillah, an AWOL sailor...

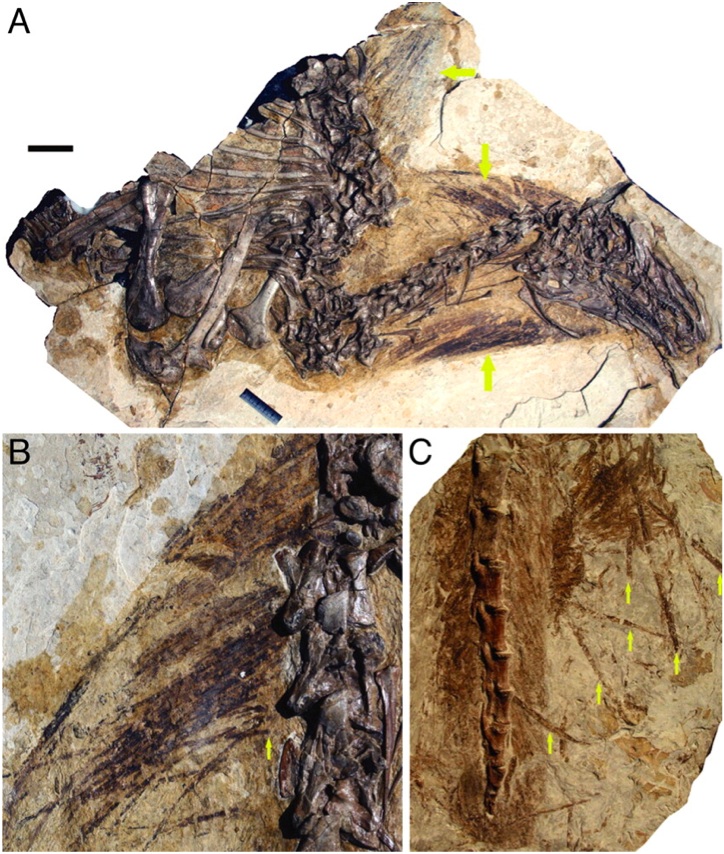

Non-coding DNA Function... Surprising?

Non-coding DNA Function... Surprising?The existence of functional, non-protein-coding DNA is all too frequently portrayed as a great...

Yep, This Should Get You Fired

Yep, This Should Get You FiredAn Ohio 8th-grade creationist science teacher with a habit of branding crosses on his students'...

No, There Are No Alien Bar Codes In Our Genomes

No, There Are No Alien Bar Codes In Our GenomesEven for a physicist, this is bad: Larry Moran, in preparation for the appropriate dose of ridicule...