How can we share 98% of our DNA with a chimpanzee and still be so different? One of the biggest biological surprises found in our genomes is that chimps, mice, and even flies don't differ very much from us in either number or types of genes. What makes the many diverse animal groups different is not what genes they have; the secret is in how those genes are used.

Something similar takes place inside ourselves: nearly every one of our cells carries the exact same DNA, and yet some cells transmit electrical signals in the brain, while others break down toxic compounds in the liver. How do you get such different cells from the same DNA? Again, the secret lies in how genes are regulated.

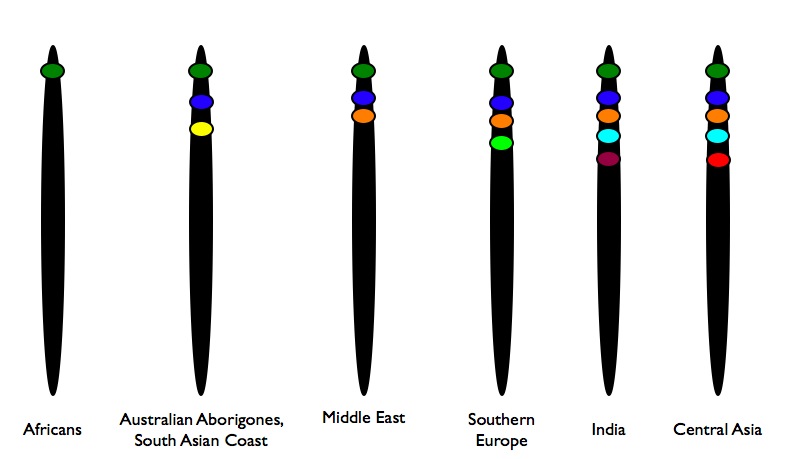

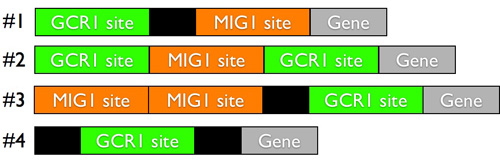

It should be no surprise then that gene regulation has been the subject of intense study. Most of these studies have focused on taking known genes and describing how they are regulated, but what biologists would really like to do is

predict how an unfamiliar gene is controlled, simply by analyzing that gene's regulatory DNA. Once we can predict how genes are regulated, we're not far away from being able to design new regulatory DNA, which we can use to control the fate of stem cells, manipulate dosing in gene therapy, and design microbes that make better biofuels or degrade toxic waste. A

new report in Nature describes an innovative new way to learn the logic of gene regulation.

Melville on Science vs. Creation Myth

Melville on Science vs. Creation Myth Non-coding DNA Function... Surprising?

Non-coding DNA Function... Surprising? Yep, This Should Get You Fired

Yep, This Should Get You Fired No, There Are No Alien Bar Codes In Our Genomes

No, There Are No Alien Bar Codes In Our Genomes