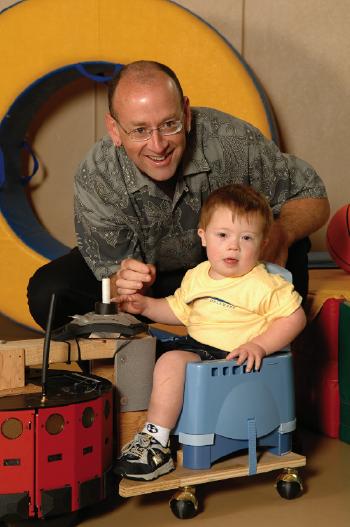

Babies driving robots. It sounds silly but it is actually the focus of innovative research being conducted at the University of Delaware to help infants with special needs.

Two researchers – James C. (Cole) Galloway, associate professor of physical therapy, and Sunil Agrawal, professor of mechanical engineering – have outfitted kid-size robots to provide mobility to children who are unable to fully explore the world on their own.

The work is important because much of infant development, both of the brain and behavior, emerges from the thousands of experiences each day that arise as babies independently move and explore their world. This is the concept of “embodied development,” Galloway said.

Infants with Down Syndrome, cerebral palsy, autism and other disorders can have mobility limitations that disconnect them from the ongoing exploration that their peers enjoy.

“If these infants were adults, therapists would have options of assistive technology such as power wheelchairs,” Galloway said. “Currently, children with significant mobility impairments are not offered power mobility until they are 5-6 years of age, or older. This delay in mobility is particularly disturbing when you consider the rapid brain development during infancy. Their actions, feelings and thinking all shape their own brain’s development. Babies literally build their own brains through their exploration and learning in the complex world.”

When a baby starts crawling and walking, everything changes for everyone involved. “Now consider the negative impact of a half decade of immobility for an infant with already delayed development,” Galloway said. “When a baby doesn’t crawl or walk, everything also changes. Immobility changes the infant, and the family. Given the need, you would think that the barriers to providing power mobility must be insurmountable. In fact, the primary barrier is safety.” Therapists and parents fear a young child in a power wheelchair might mistakenly go the wrong way, end up in a roadway and get hit by a car.

“This is, of course, understandable, and is the same fear that every parent with a newly walking infant faces. It is the solution to the safety problem that is the real barrier. The current clinical practice is to avoid power mobility until the child can follow adult commands,” Galloway said. “Your parents didn’t wait until you followed their every command before they let you walk – they held your hand, they required you to stay near them, and alerted you to obstacles in your way. This is the way infants learn real world navigation, and it is exactly these safety features that are being built into our mobile robot.”

“Our first prototype, affectionately called UD1, was designed with smart technology that addresses each of these safety issues so that infants have the opportunity to be a part of the real world environment,” Agrawal said.

The tiny robot is ringed with sensors that can determine the obstacle-free roaming space, and will either allow infants to bump obstacles or will take control from the infant and drive around the obstacle itself. The next prototype, UD2, will build on the current technology to provide additional control to a parent, teacher or other supervising adult.

“In this way, we can bind technology and human need together to remove barriers for movement in the environment,” Agrawal said.

Galloway said no one had ever tried using robots with babies – early experiments show that seven-month-olds can learn to operate the simple joystick controls – and he is passionate about the possible benefits to children with special needs of even younger ages.

“Infants with limited mobility play in one location while their peers or siblings go off on distant adventures all over the room or playground,” Galloway said. “With the robot, they become the center of attention because their classmates want to try it. We predict that this increased social interaction alone will provide an important boost in their cognitive development.”

The idea sprang from a parking lot conversation in which Agrawal approached Galloway, who he knew worked with babies with special needs, and said he might have developed something of interest. Agrawal is a robotics expert who had been developing a fleet of small, rounded robots that could work as a unit through a wireless network.

Galloway knew of Agrawal’s successes with rehabilitation robotics for adults but admitted to being anti-robot for pediatric rehabilitation at first. Galloway was convinced otherwise within minutes of his first visit to Agrawal’s laboratory. “When I saw his little robots, it was easy to envision a baby driving one,” he said. “We knew from our previous work that newly reaching infants could use a joystick to control a distant toy. This and other research strongly suggests that very young infants can be trained in real world navigation. It was a special feeling to see a potential solution to a really serious healthcare gap for young kids. There was and still is a special tingle when we think of the not so distant future. “

Thus, UD1 was born. The researchers took their robot to the UD Early Learning Center, which has a wide range of infants, a gymnasium for initial training on the robot and a varied outdoor landscape to use as a test track.

“It was a relief when we saw that the children quickly grasped the use of the joystick,” Agrawal said. “If they had just sat there or cried, it would have been back to the drawing board. But over time we have seen them gradually increase their time with the robot and the amount of distance they cover.”

The project will now move on to a second generation with more than one robot. The goal is to place multiple mobile robots with special needs infants in communities throughout Delaware and to gather data to analyze how they are used and what the children learn so that the research team can continue to make modifications.

Both note that Delaware, with its mix of urban, rural and suburban communities, is a model state for a clinical project such as this. “For a real world mobility device to emerge, we have to build it for exploring the real world experienced by infants and their families, and then rigorously study its performance in that world,” Galloway said.

Both said the project will significantly expand understanding of young infants’ learning capacity and provide a model for tracking the development of real world exploration with laboratory quality data.

They believe the training, robot design and new technology derived from the project will provide the foundation for the first generation of safe, smart vehicles for infants born with mobility impairments.

They want the UD1 product to be light enough for moms to stow in a car trunk, and robust enough for babies to use in the home, yard and playground, and maybe even the beach.

This interdisciplinary project is bringing together students and researchers from fields that have had little or no interaction: engineering, early childhood education and pediatric therapy.

“The research, educational and health care impact is hard to overestimate, given the critical nature of early development, the relatively short time to prepare special needs infants to enter mainstream education and the complete lack of power mobility early in life,” Galloway said. “This project has so many positives, and is of interest to so many in the community. We are encouraging everyone interested in special needs infants to get involved – from parents to policy makers. We are thinking locally and globally at the same time.”

He added, “Although there are special needs kids in every community, you have never seen a special needs child driving themselves down Main Street in Newark, and neither has anyone else in any community anywhere. They, and often their families, are hidden citizens. We predict that very soon that will change in Newark, and then across Delaware, and then who knows. But time is of the essence because there is a baby being born right now who could use this today. That is the race we are in, so back to work.”

Agrawal, who directs the UD robotics laboratory, received his doctorate in mechanical engineering in 1990 from Stanford University, where he was a research assistant in the university's robotics laboratory. He taught and conducted research at Ohio University from 1990 until 1996, when he joined the UD faculty. He received his bachelor's degree from the Indian Institute of Technology in Kanpur and his master's degree from Ohio State University.

Galloway, who directs the UD Infant Motor Behavior Laboratory, received his doctorate in physiological sciences from the University of Arizona in 1998 and joined the UD faculty in 2000. He received bachelor’s degrees in exercise science and biology from the University of Southern Mississippi in 1987 and in physical therapy from Virginia Commonwealth University in 1989.

Providing important technical support to the project is Ji-Chul Ryu, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Mechanical Engineering with expertise in the planning and control of mobile robots.

- University of Delaware

Comments