The "Basel-Gasfabrik" Celtic settlement, at the present day site of Novartis, was inhabited around 100 B.C. and is one of the most significant Celtic sites in Central Europe.

A team recently examined samples from the backfill of 2000 year-old storage and cellar pits from the Iron Age and found the durable eggs of intestinal parasites like roundworms (Ascaris sp.), whipworms, (Trichuris sp.) and liver flukes (Fasciola sp.).

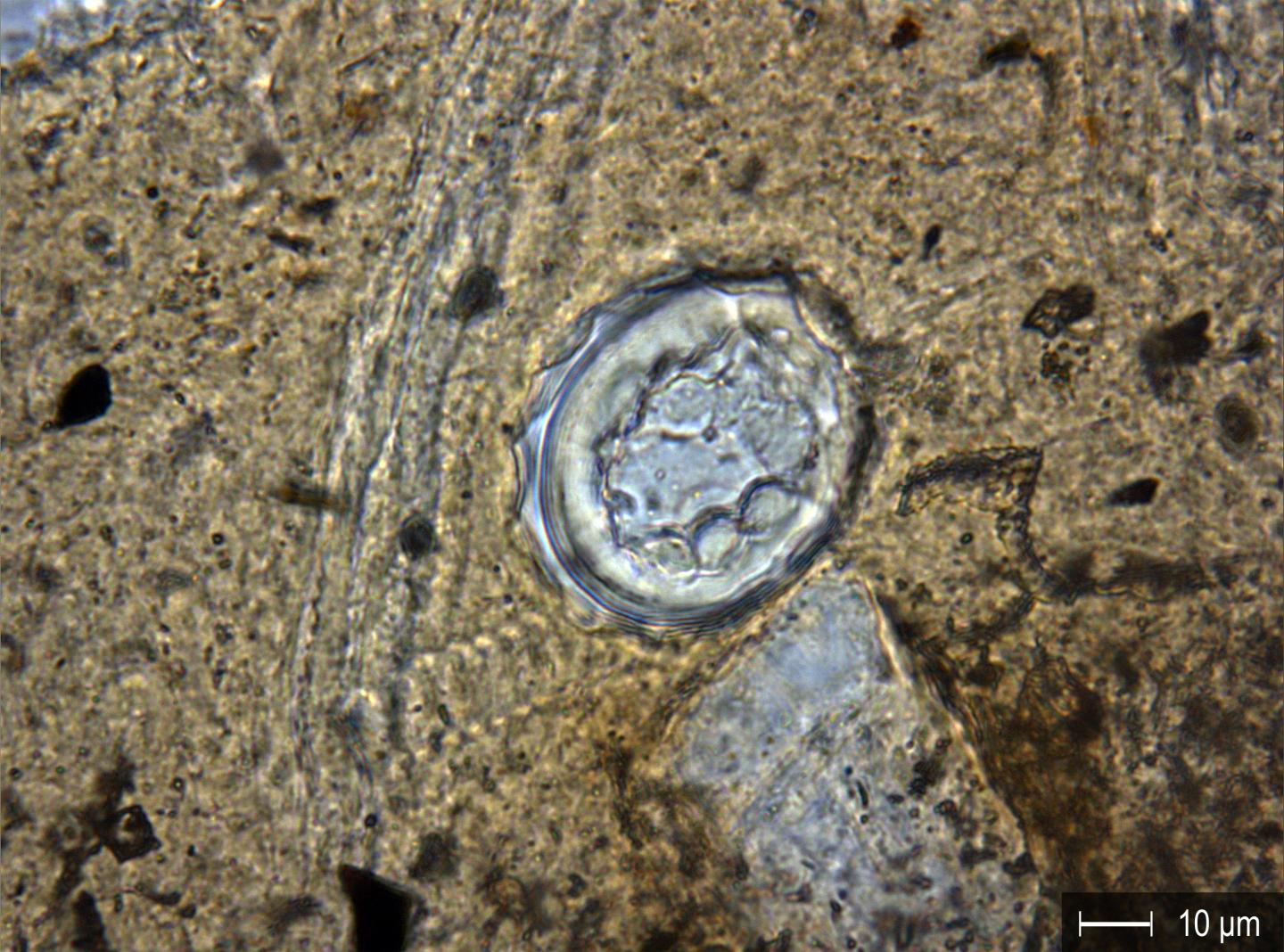

The presence of the parasite eggs was not established by wet sieving of the soil samples, instead they applied a geoarchaeology-based method using micromorphological thin sections, which enable the parasite eggs to be captured directly in their original settings. The thin sections were prepared from soil samples embedded in synthetic resin, thus permitting the researchers to determine the number and exact location of the eggs at their site of origin in the sediments of the pits. This offered new insights into diseases triggered by parasites in the Iron Age settlement.

A roundworm egg (Ascaris sp.) with a typical undulating membrane. Credit: University of Basel, IPAS

Poor sanitary conditions

The eggs of the Iron Age parasites originate from preserved human and animal excrement (coprolites) and show that some individuals were host to several parasites at the same time. Furthermore, the parasite eggs were distributed throughout the former topsoil, which points to the waste management practiced for this special type of 'refuse'. It may, for example, have been used as fertilizer for the settlement's vegetable gardens. As liver flukes require freshwater snails to serve as intermediate hosts, it is conceivable that this type of parasite was introduced via livestock brought in from the surrounding areas to supply meat for the settlement's population.

The archaeologists also used the microscopic slides to show that the eggs of the intestinal parasites were washed out with water and dispersed in the soil. This suggests poor sanitary conditions in the former Celtic community, in which humans and animals lived side by side. At the same time, the distribution of the parasite eggs indicates possible routes of transmission within and between species.

The research project conducted by the IPAS (University of Basel), and Archäologische Bodenforschung Basel-Stadt was also supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Freiwillige Akademische Gesellschaft Basel.

Citation: Sandra L. Pichler, Christine Pümpin, David Brönnimann, Philippe Rentzel

Life in the Proto-Urban Style: The identification of parasite eggs in micromorphological thin sections from the Swiss Basel-Gasfabrik late Iron Age settlement. Journal of Archaeological Science (2014) | doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2013.12.002

Comments