An international team of scientists, led by researchers at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, have identified the genes encoding a molecule that famously defines Group A Streptococcus (strep), a pathogenic bacterial species responsible for more than 700 million infections worldwide each year.

The findings, published online in the June 11 issue of Cell Host&Microbe, shed new light on how strep bacteria resists the human immune system and provides a new strategy for developing a safe and broadly effective vaccine against strep throat, necrotizing fasciitis (flesh-eating disease) and rheumatic heart disease.

"Most people experience one or more painful strep throat infections as a child or young adult," said senior author Victor Nizet, MD, professor of pediatrics and pharmacy. "Developing a broadly effective and safe strep vaccine could prevent this suffering and reduce lost time and productivity at school and work, estimated to cost $2 billion annually."

Efforts to develop such a vaccine have been significantly hindered by complexities in how the human immune system reacts to the bacterial pathogen. Specifically, some patients with strep infections produce antibodies that cross-react with their own heart valve tissue, leading to rheumatic fever and heart damage. Though rare in the United States, rheumatic fever remains common in some developing countries and causes significant disability and death.

The Cell Host & Microbe study suggests a way to circumvent the damaging autoimmune response triggered by strep. Specifically, the researchers noted that the cell wall of strep is composed primarily of a single molecule known as the group A carbohydrate (or GAC) which, in turn, is built from repeating units of the bacterial sugar rhamnose and the human-like sugar N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc).

Previous research has indicated that GlcNAc sugars present in GAC may be responsible for triggering production of heart-damaging antibodies in some patients. Nizet said the latest findings corroborate this model, and suggest that eliminating the pathogen's ability to add GlcNAc sugars to GAC could be the basis for a safe vaccine.

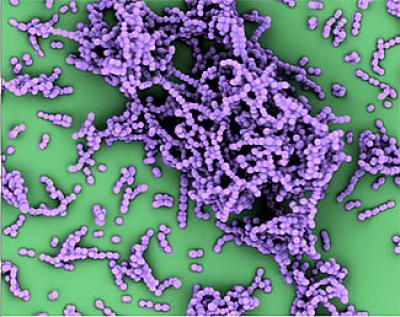

This is an electron micrograph, in false color, of group A Streptococcus bacteria.

(Photo Credit: UC San Diego School of Medicine)

"In this study, we discovered the strep genes responsible for the biosynthesis and assembly of GAC, the very molecule that defines the pathogen in clinical diagnosis," said first author Nina van Sorge, PharmD, PhD, a former postdoctoral fellow at UC San Diego who now leads her own laboratory at Utrecht University Medical Center in the Netherlands. "This discovery allowed us to generate mutant bacterial strains and study the contribution of GAC to strep disease."

The researchers found that a mutant strep strain lacking the human-like GlcNAc sugar on the GAC molecule exhibited normal bacterial growth and expressed key proteins known to be associated with strep virulence, but was easily killed when exposed to human white blood cells or serum. The mutant strep bacteria also lost the ability to produce severe disease in animal infection models

"Our studies showed that the GlcNAc sugar of GAC is a critical virulence factor allowing strep to spread in the blood and tissues," van Sorge said. "This is likely important for the rare, but deadly, complications of strep infection such as pneumonia, necrotizing fasciitis and toxic shock syndrome."

The researchers also identified a way to remove the problematic GlcNAc sugar so that a mutant form of the bacteria with only rhamnose-containing GAC could be purified and tested as a vaccine antigen.

"We showed that antibodies produced against mutant GAC antigen helped human white blood cells kill the pathogen and protected mice from lethal strep infection," said Jason Cole, PhD, a visiting project scientist from the University of Queensland, Australia, and co-lead author of the paper. "Because GAC is present in all strep strains, this may represent a safer antigen for inclusion in a universal strep vaccine."

Researchers plan to assess the new modified antigen against other candidates in advanced strep throat vaccine tests in nonhuman primates beginning later this year in Atlanta, Georgia, funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

"It is satisfying to find that a fundamental observation regarding the genetics and biochemistry of the pathogen can have implications not only for strep disease pathogenesis, but also for vaccine design," Nizet said.

Comments