When domesticated agriculture was invented, it took off and revolutionized human expansion but a study of ceramic pots from 15 sites dating to around 4,000 B.C. shows humans may have undergone a gradual rather than an abrupt transition from fishing, hunting and gathering to farming. The researchers analyzed the cooking residues preserved in 133 ceramic vessels from the Western Baltic regions of Northern Europe to establish whether these residues were from terrestrial, marine or freshwater organisms.

The research team found that fish and other aquatic resources continued to be exploited after the advent of farming and domestication, with pots from coastal locations containing residues enriched in a form of carbon found in marine organisms.

Around one-fifth of coastal pots contained other biochemical traces of aquatic organisms, including fats and oils absent in terrestrial animals and plants. At inland sites, 28 percent of pots contained residues from aquatic organisms, which appeared to be from freshwater fish.

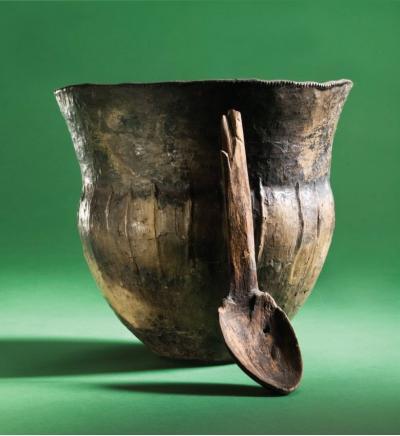

Artifacts thought to have been votive offerings by the earliest farming communities who lived in this area. Chemical analysis of charred food residues preserved on inside of a number of these vessels show they were used for processing freshwater fish,which supplemented their fledgling agricultural economy. Image courtesy of Anders Fischer

Lead author Dr Oliver Craig, of the Department of Archaeology at York, said, "This research provides clear evidence people across the Western Baltic continued to exploit marine and freshwater resources despite the arrival of domesticated animals and plants. Although farming was introduced rapidly across this region, it may not have caused such a dramatic shift from hunter-gatherer life as we previously thought."

Carl Heron, Professor of Archaeological Sciences at the University of Bradford, said, "Our data set represents the first large scale study combining a wide range of molecular evidence and single-compound isotope data to discriminate terrestrial, marine and freshwater resources processed in archaeological ceramics and it provides a template for future investigations into how people used pots in the past."

Published in the latest edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Comments