On the Kelvin Scale, the absolute temperature used by physicists, it is not possible to get colder than zero degrees kelvin. The physical meaning of the temperature of a gas is determined by chaos, the disordered movement of its particles. The colder the gas, the slower the particles and at zero kelvin (-459.67 F, -273 C) the particles stop moving and all disorder disappears. That is why it is called absolute zero.

But physicists at the Ludwig-Maximilians University Munich and the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics in Garching have created an atomic gas that has negative Kelvin values, with several apparently absurd consequences: The atoms in the gas attract each other and give rise to a negative pressure but the gas does not collapse – behavior that will make proponents of the dark energy hypothesis happy. The blanket term for the elusive force(s) hypothesized to accelerate the expansion of the universe came into being because the cosmos should contract due the gravitational attraction between all masses but does not. In a new experiment, the atoms in the gas do not repel each other as in a usual gas, but instead interact attractively - the atoms exert a negative instead of a positive pressure. The atom cloud wants to contract and should – just as would be expected for the universe under the effect of gravity - but because of its negative temperature this does not happen. The gas is saved from collapse just like perhaps the universe is.

In such a negative absolute temperature state, impossible heat engines like a combustion engine with a thermodynamic efficiency of over 100% could also be realized. Now that's clean energy!

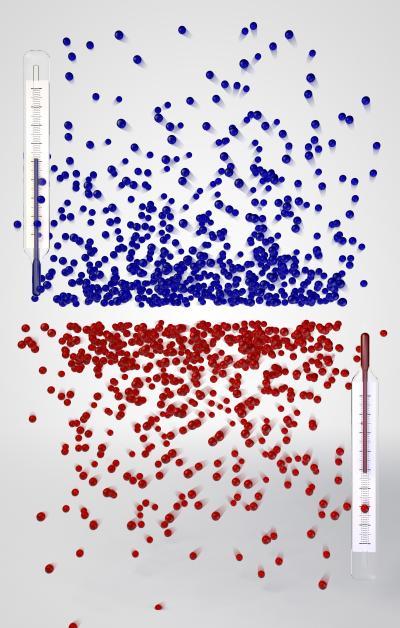

Take boiling water as an example. To go from room temperature to boiling, energy needs to be added. As the water heats up, the water molecules increase their kinetic energy over time and move faster and faster on average. The individual molecules possess different kinetic energies – from very slow to very fast and low-energy states are more likely than high-energy states so only a few particles move really fast. This is called the Boltzmann distribution and the physicists behind the new study say they have created a gas in which this distribution is precisely inverted: many particles possess high energies and only a few have low energies. This inversion of the energy distribution means that the particles have assumed a negative absolute temperature.

"The inverted Boltzmann distribution is the hallmark of negative absolute temperature; and this is what we have achieved," says Ulrich Schneider. "Yet the gas is not colder than zero kelvin, but hotter," as the physicist explains: "It is even hotter than at any positive temperature – the temperature scale simply does not end at infinity, but jumps to negative values instead."

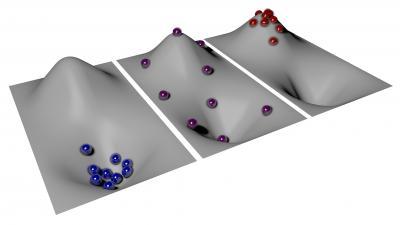

Negative absolute temperature is not like going below zero on a cold day. It can instead best be understood by imagining rolling spheres in a hilly landscape, where the valleys stand for a low potential energy and the hills for a high one. The faster the spheres move, the higher their kinetic energy as well: starting at positive temperatures and increasing the total energy of the spheres by heating them up means the spheres will increasingly spread into regions of high energy. If it were possible to heat the spheres to infinite temperature, there would be an equal probability of finding them at any point in the landscape, irrespective of the potential energy.

If you could now add even more energy and thereby heat the spheres even further, they would preferably gather at high-energy states and would be even hotter than at infinite temperature. The Boltzmann distribution would be inverted, and the temperature therefore negative. At first sight it may sound strange that a negative absolute temperature is hotter than a positive one. This is simply a consequence of the historic definition of absolute temperature, however; if it were defined differently, this apparent contradiction would not exist.

Temperature as a game of marbles: The Boltzmann distribution states how many particles have which energy, and can be illustrated with the aid of spheres that are distributed in a hilly landscape. At positive temperatures (left image), as are common in everyday life, most spheres lie in the valley at minimum potential energy and barely move; they therefore also possess minimum kinetic energy. States with low total energy are therefore more likely than those with high total energy -- the usual Boltzmann distribution. At infinite temperature (center image) the spheres are spread evenly over low and high energies in an identical landscape. Here, all energy states are equally probable. At negative temperatures (right image), however, most spheres move on top of the hill, at the upper limit of the potential energy. Their kinetic energy is also maximum. Energy states with high total energy thus occur more frequently than those with low total energy -- the Boltzmann distribution is inverted. Credit: LMU and MPG Munich

This inversion of the population of energy states is not possible in water or any other natural system as the system would need to absorb an infinite amount of energy – an impossible feat! However, if the particles possess an upper limit for their energy, such as the top of the hill in the potential energy landscape, the situation will be completely different. The researchers in Immanuel Bloch's and Ulrich Schneider's research group say they have now realized such a system of an atomic gas with an upper energy limit in their laboratory, following theoretical proposals by Allard Mosk and Achim Rosch.

Hot minus temperatures: At a negative absolute temperature the energy distribution of particles inverts in comparison to a positive temperature. Many particles then have a high energy and few a low one. This corresponds to a temperature which is hotter than one that is infinitely high, where the particles are distributed equally over all energies. A negative Kelvin temperature can only be achieved experimentally if the energy has an upper limit, just as non-moving particles form a lower limit for the kinetic energy at positive temperatures -- physicists at the LMU and the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics have now achieved this. Credit: LMU and MPG Munich

For their experiment, the scientists first cooled a hundred thousand atoms in a vacuum chamber to a positive temperature of a few billionths of a Kelvin and captured them in optical traps made of laser beams.

The surrounding ultrahigh vacuum guarantees that the atoms are perfectly thermally insulated from the environment and the laser beams create an optical lattice, in which the atoms are arranged regularly at lattice sites. In this lattice, the atoms can still move from site to site via the tunnel effect, yet their kinetic energy has an upper limit and therefore possesses the required upper energy limit. Temperature, however, relates not only to kinetic energy, but to the total energy of the particles, which in this case includes interaction and potential energy.

The system also sets a limit to both of these. The physicists then take the atoms to this upper boundary of the total energy – thus realizing a negative temperature, at minus a few billionths of a kelvin.

At negative temperatures an engine can do more work

If spheres possess a positive temperature and lie in a valley at minimum potential energy, this state is obviously stable – this is nature as we know it. If the spheres are located on top of a hill at maximum potential energy, they will usually roll down and thereby convert their potential energy into kinetic energy.

"If the spheres are at a negative temperature, however, their kinetic energy will already be so large that it cannot increase further," explains Simon Braun, a doctoral student in the research group. "The spheres thus cannot roll down, and they stay on top of the hill. The energy limit therefore renders the system stable!" The negative temperature state in their experiment is indeed just as stable as a positive temperature state.

"We have thus created the first negative absolute temperature state for moving particles," adds Braun.

Matter at negative absolute temperature has a whole range of astounding consequences: with its help, one could create heat engines such as combustion engines with an efficiency of more than 100%. This does not mean, however, that the law of energy conservation is violated. Instead, the engine could not only absorb energy from the hotter medium, and thus do work, but, in contrast to the usual case, from the colder medium as well.

At purely positive temperatures, the colder medium inevitably heats up in contrast, therefore absorbing a portion of the energy of the hot medium and thereby limits the efficiency. If the hot medium has a negative temperature, it is possible to absorb energy from both media simultaneously. The work performed by the engine is therefore greater than the energy taken from the hotter medium alone – the efficiency is over 100 percent.

Comments