Cells from eukaryotic organisms can also be modified for research or to fight disease. To achieve these and other worthy goals, the ability to precisely edit the instructions contained within a target’s genome is a must. A powerful new tool for genome editing and gene regulation has emerged in the form of a family of enzymes known as Cas9, which plays a critical role in the bacterial immune system.

Cas9 should become an even more valuable tool with the creation of the first detailed picture of its three-dimensional shape by researchers with the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the University of California (UC) Berkeley.

Biochemist Jennifer Doudna and biophysicist Eva Nogales led an international collaboration that used x-ray crystallography to produce 2.6 and 2.2 angstrom (Å) resolution crystal structure images of two major types of Cas9 enzymes. The collaboration then used single-particle electron microscopy to reveal how Cas9 partners with its guide RNA to interact with target DNA. The results point the way to the rational design of new and improved versions of Cas9 enzymes for basic research and genetic engineering.

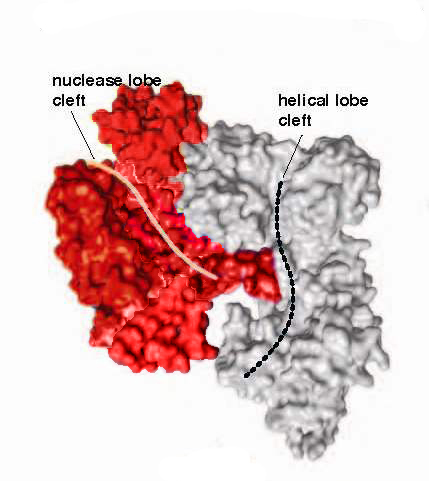

The crystal structure of SpyCas9 features a nuclease domain lobe (red) and an alpha-helical lobe (gray) each with a nucleic acid binding cleft that becomes functionalized when Cas9 binds to guide RNA. Credit: LBL

“The combination of x-ray protein crystallography and electron microscopy single-particle analysis showed us something that was not anticipated,” says Nogales. “The Cas9 protein, on its own, exists in an inactive state, but upon binding to the guide RNA, the Cas9 protein undergoes a radical change in its three-dimensional structure that enables it to engage with the target DNA.”

“Because we now have high-resolution structures of the two major types of Cas9 proteins, we can start to see how this family of bacterial enzymes has evolved,” Doudna says. “We see that the two structures are quite different from each other outside of their catalytic domains, suggesting an interesting structural plasticity that could explain how Cas9 is able to use different kinds of guide RNAs. Also, the differences in the two structures suggest that it may be possible to engineer smaller Cas9 variants and still retain function, an important goal for some genome engineering applications.”

Bacteria face a never-ending onslaught from viruses and invading strands of nucleic acid known as plasmids. To survive, they deploy a variety of defense mechanisms, including an adaptive-type nucleic acid-based immune system that revolves around a genetic element known as CRISPR, which stands for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats. Through the combination of CRISPR and squads of CRISPR-associated or “Cas” proteins, microbes are able to utilize small customized RNA molecules as guides to target and silence critical portions of an invader’s genetic message and also to acquire immunity from similar invasions in the future.

Cas9 is a family of RNA-guided bacterial endonucleases employed by Type II CRISPR systems to recognize and cleave double-stranded DNA at site-specific sequences. Genetic engineers have begun harnessing Cas9 for genome editing and gene regulation in many eukaryotic organisms. However, despite the successes to date, the technology has yet to reach its full potential because until now the structural basis for guide RNA recognition and DNA targeting by Cas9 has been unknown.

Doudna, Nogales and their collaborators addressed this knowledge deficit by first solving the three-dimensional crystal structures of two Cas9 proteins, representing large and small versions, from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpyCas) and Actinomyces naeslundii (AnaCas9) respectively. Using protein crystallography beamlines at Berkeley Lab’s Advanced Light Source and the Paul Scherer Institute’s Swiss Light Source, the collaboration discovered that despite significant differences outside of their catalytic domains, all members of the Cas9 family share the same structural core.

The high resolution images showed this core to feature a clam-shaped architecture with two major lobes – a nuclease domain lobe and an alpha-helical lobe. Both lobes contained conserved clefts that become functional in nucleic acid binding.

“Our understanding of Cas9’s structure was not complete with only the x-ray data because the protein in the crystals had been trapped in a state without its associated guide RNA,” says Sam Sternberg, a member of Doudna’s research group and a co-author of thepaper. “Understanding how RNA-guided Cas9 targets matching DNA sequences for genome engineering and how this reaction and its specificity might be improved required an understanding of how the shape of Cas9 changes when it interacts with guide RNA, and when a matching DNA target sequence is bound.”

The collaboration employed negative-staining electron microscopy to visualize the Cas9 protein bound to either guide RNA, or both RNA and target DNA. The structures revealed that the guide RNA binding structurally activates Cas9 by creating a channel between the two main lobes of the protein that functions as the DNA-binding interface.

“Our single particle electron microscopy analysis reveals the importance of guide-RNA for the conversion of Cas9 into a structurally-activated state,” says David Taylor, a joint member of Doudna’s and Nogales’s research groups and another co-author of the paper. “The results underline that, in addition to sequence complementarity, other features of the guide-RNA must be considered when employing this technology.”

Published in Science. Source: Lawrence Berkeley National Lab

Comments