Infrasonic waves from the meteor that broke up over over Chelyabinsk in Russia's Ural mountains last week were the largest ever recorded by the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization's (CTBTO) International Monitoring System. The blast was detected by 17 infrasound stations in the CTBTO's network, which tracks atomic blasts across the planet. The furthest station to record the sub-audible sound was 15,000 km away in Antarctica.

Infrasound has been used as part of the CTBTO's tools to detect atomic blasts since April 2001 when the first station came online in Germany. It is low frequency sound with a range of less than 10 Hz. People cannot hear the low frequency waves that were emitted but they were recorded by the CTBTO's network of sensors as they traveled across continents.

The origin of the low frequency sound waves from the blast was estimated at 03:22 GMT on 15 February 2013. "We saw straight away that the event would be huge, in the same order as the Sulawesi event from 2009. The observations are some of the largest that CTBTO's infrasound stations have detected," CTBTO acoustic scientist Pierrick Mialle said.

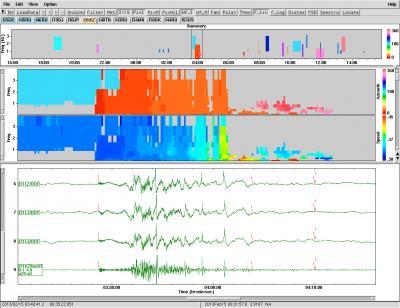

Infrasonic waves from the meteor that broke up over Russia's Ural mountains on 15 Feb. 2013 were recorded by the CTBTO's International Monitoring System. The image shows a visual representation of the infrasound waves and computer attributes of the fireball as it was recorded by the CTBTO station in Kazakhstan and processed by the CTBTO's International Data Centre. Credit: CTBTO

Until last week, the bolide explosion above Sulawesi, Indonesia, in October 2009 was the largest infrasound event registered by 15 stations in the CTBTO's network.

"We know it's not a fixed explosion because we can see the change in direction as the meteorite moves towards the earth. It's not a single explosion, it's burning, traveling faster than the speed of sound. That's how we distinguish it from mining blasts or volcanic eruptions.

"Scientists all around the world will be using the CTBTO's data in the next months and year to come, to better understand this phenomena and to learn more about the altitude, energy released and how the meteor broke up," Mialle said.

The infrasound station at Qaanaaq, Greenland was among those that recorded the meteor explosion in Russia. There are currently 45 infrasound stations in the CTBTO's network that measure micropressure changes in the atmosphere generated by infrasonic waves. Like meteor blasts, atomic explosions produce their own distinctive, low frequency sound waves that can travel across continents.

Infrasound is one of four technologies (including seismic, hydroacoustic and radionuclide) the CTBTO uses to monitor the globe for violations of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty that bans all nuclear explosions.

Seismic signals from the meteor were also detected at several Kazakh stations close to the explosion and impact area. In the accompanying video file, you can listen to the audio files of the infrasound recording after it has been filtered and the signal accelerated.

Days before the meteor on 12 February 2013, the CTBTO's seismic network detected an unusual seismic event in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), which measured 4.9 in magnitude. Later that morning, the DPRK announced that it had conducted a nuclear test. The event was registered by 94 seismic stations and two infrasound stations in the CTBTO's network. The data processing and analysis are designed to weed out natural events and focus on those events that might be explosions, including nuclear explosions.

17 infrasound stations in the CTBTO's network detected the infrasonic waves from the meteor that broke up over Russia's Ural mountains on 15 Feb. 2013. The furthest station to record the sub-audible sound was 15,000km away in Antarctica. Credit: CTBTO

Comments