Words are so 20th century. The 21st century could belong to brains communicating directly with each other.

Researchers have successfully replicated a direct brain-to-brain connection between pairs of people. In the newly published paper, which involved six people, researchers were able to transmit the signals from one person's brain over the Internet and use these signals to control the hand motions of another person within a split second of sending that signal.

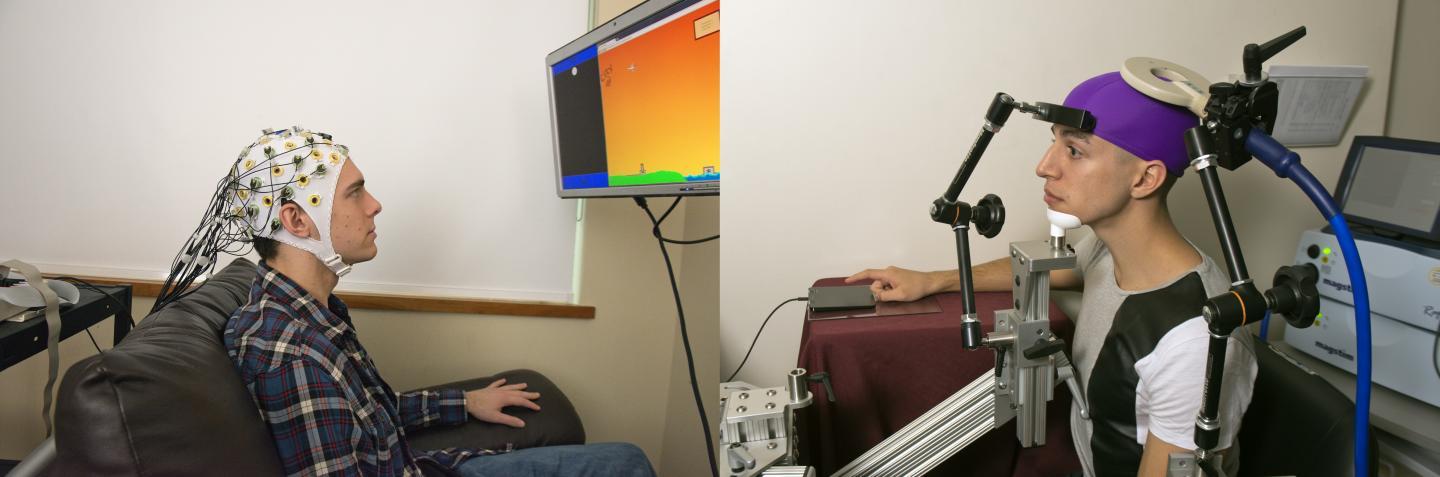

The research team combined two kinds of noninvasive instruments and fine-tuned software to connect two human brains in real time. The process is fairly straightforward. One participant is hooked to an electroencephalography machine that reads brain activity and sends electrical pulses via the Web to the second participant, who is wearing a swim cap with a transcranial magnetic stimulation coil placed near the part of the brain that controls hand movements.

The sender is hooked to an electroencephalography machine that reads brain activity. A computer processes the brain signals and sends electrical pulses via the Web to the receiver across campus. Credit: U of Washington

"The new study brings our brain-to-brain interfacing paradigm from an initial demonstration to something that is closer to a deliverable technology," said co-author Andrea Stocco, a research assistant professor of psychology and a researcher at UW's Institute for Learning&Brain Sciences. "Now we have replicated our methods and know that they can work reliably with walk-in participants."

Using this setup, one person can send a command to move the hand of the other by simply thinking about that hand movement.

The UW study involved three pairs of participants. Each pair included a sender and a receiver with different roles and constraints. They sat in separate buildings on campus about a half mile apart and were unable to interact with each other in any way – except for the link between their brains.

UW students Darby Losey, left, and Jose Ceballos are positioned in two different buildings on campus as they would be during a brain-to-brain interface demonstration. The sender, left, thinks about firing a cannon at various points throughout a computer game. That signal is sent over the Web directly to the brain of the receiver, right, whose hand hits a touchpad to fire the cannon. Credit: U of Washington

Each sender was in front of a computer game in which he or she had to defend a city by firing a cannon and intercepting rockets launched by a pirate ship. But because the senders could not physically interact with the game, the only way they could defend the city was by thinking about moving their hand to fire the cannon.

Across campus, each receiver sat wearing headphones in a dark room – with no ability to see the computer game – with the right hand positioned over the only touchpad that could actually fire the cannon. If the brain-to-brain interface was successful, the receiver's hand would twitch, pressing the touchpad and firing the cannon that was displayed on the sender's computer screen across campus.

Researchers found that accuracy varied among the pairs, ranging from 25 to 83 percent. Misses mostly were due to a sender failing to accurately execute the thought to send the "fire" command. The researchers also were able to quantify the exact amount of information that was transferred between the two brains.

Another research team from the company Starlab in Barcelona, Spain, recently published results in the same journal showing direct communication between two human brains, but that study only tested one sender brain instead of different pairs of study participants and was conducted offline instead of in real time over the Web.

A transcranial magnetic stimulation coil is placed over the part of the brain that controls the receiver's right hand movements. Credit: U of Washington

Now, with a new $1 million grant from the W.M. Keck Foundation, the UW research team is taking the work a step further in an attempt to decode and transmit more complex brain processes.

With the new funding, the research team will expand the types of information that can be transferred from brain to brain, including more complex visual and psychological phenomena such as concepts, thoughts and rules.

They're also exploring how to influence brain waves that correspond with alertness or sleepiness. Eventually, for example, the brain of a sleepy airplane pilot dozing off at the controls could stimulate the copilot's brain to become more alert.

The project could also eventually lead to "brain tutoring," in which knowledge is transferred directly from the brain of a teacher to a student.

"Imagine someone who's a brilliant scientist but not a brilliant teacher. Complex knowledge is hard to explain – we're limited by language," said co-author Chantel Prat, a faculty member at the Institute for Learning & Brain Sciences and a UW assistant professor of psychology.

Comments