Evaporative cooling has been used to cool atoms to extraordinarily low temperatures. The process was used in 1995 to create a new state of matter, the Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC) of rubidium atoms (see Nobel laureate Carl Wieman and his Science 2.0 articles here), which was so revolutionary and unnatural that BEC atoms travel at a rate of only three feet per hour. Now in its 50th year, Joint Institute for Laboratory Astrophysics (JILA) physicists have met a goal once bordering on the impossible - they have chilled a gas of molecules to very low temperatures by adapting the familiar process by which a hot cup of coffee cools

This is the first time evaporative cooling has been achieved with molecules - two different atoms bonded together.

They cooled about 1 million hydroxyl radicals, each composed of one oxygen atom and one hydrogen atom (OH), from about 50 milliKelvin (mK) to 5 mK, five-thousandths of a degree above absolute zero. The 70-millisecond process also made the cloud 1,000 times denser and cooler. With just a tad more cooling to below 1 mK, the new method may enable advances in ultracold chemistry, quantum simulators to mimic poorly understood physical systems, and perhaps even a BEC made of highly reactive molecules. These two steps have been under development for a decade.

The same JILA group previously used magnetic fields and lasers to chill molecules made of potassium and rubidium atoms to temperatures below 1 microKelvin. But the new work demonstrates a more widely usable method for cooling molecules that is potentially applicable to a wide range of chemically interesting species.

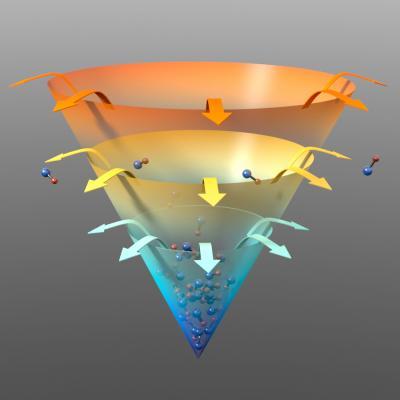

JILA researchers developed a new magnetic trap and a new technique to achieve "evaporative cooling" of hydroxyl molecules (one hydrogen atom bonded to one oxygen atom). A microwave pulse at a specific frequency converts hot molecules inside the trap to a slightly different energy state. A small electric field is pulsed on briefly to destabilize and eject these converted molecules from the trap. As the microwave frequency is slowly altered, molecules distributed inside the trap (which has a varied magnetic field strength) are progressively converted and removed from the top of the trap, where molecules are hotter, to the bottom, where molecules are cooler. Credit: Baxley and Ye Group/JILA

JILA is a joint institute of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the University of Colorado (CU) Boulder.

"OH is a hugely important species for atmospheric and combustion dynamics," says JILA/NIST Fellow Jun Ye, the group leader. "It is one of the most prominently studied molecules in physical chemistry. Now with OH molecules entering the ultracold regime, in addition to potassium-rubidium molecules, a new era in physical chemistry will be upon us in the near future."

The results are the first to be published from the first experiments conducted in JILA's new X-Wing, which opened earlier this year. JILA theorist John Bohn collaborated with Ye's group.

In evaporative cooling, particles with greater-than-average energy depart, leaving a cooler and denser system behind. Unlike coffee, however, the trapped hydroxyl molecules have to be tightly controlled and manipulated for the process to work. If too many particles react rather than just bounce off each other, they overheat the system. Until now, this was widely seen as a barrier to evaporative cooling of molecules. Molecules are more complicated than atoms in their energy structures and physical motions, making them far more difficult to control.

To achieve their landmark result, Ye's group developed a new type of trap that uses structured magnetic fields to contain the hydroxyl molecules, coupled with finely tuned electromagnetic pulses that tweak the molecules' energy states to make them either more or less susceptible to the trap. The system allows scientists not only to control the release of the hotter, more energetic molecules from the collection, but also to choose which locations within the trap are affected, and which molecular energies to cull. The result is an extremely fine level of control over the cooling system, gradually ejecting molecules that are physically deeper and relatively cooler than before.

JILA scientists say it appears feasible to cool OH molecules to even colder temperatures, perhaps to a point where all the molecules behave alike, forming the equivalent of a giant "super molecule." This would enable scientists to finally learn some of the elusive basics of how molecules interact and develop novel ways to control chemical reactions, potentially benefitting atmospheric and combustion science, among other fields.

Comments