In wrestling, we were always taught to watch the opponent's hips - because their head and their eyes were going to try and fake you out but hips don't lie.

Likewise, if you think that you can use facial expressions to determine if someone has just won the lottery or lost everything in the stock market, researchers say it just doesn't work that way. Rather, they found that body language provides a better cue in trying to judge whether an observed subject has undergone strong positive or negative experiences.

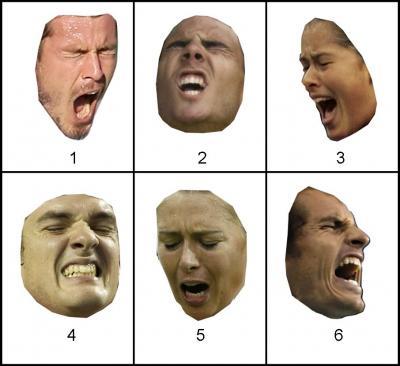

In a new paper, psychologists showed that viewers in test groups were baffled when shown photographs of people who were undergoing real-life, highly intense positive and negative experiences. When the viewers were asked to judge the emotional valences of the faces they were shown - the positivity or negativity of the faces - their guesses were no better than...guesses. They fell within the realm of chance.

In setting out to test the perception of highly intense faces, the researchers presented test groups with photos of dozens of highly intense facial expressions in a variety of real-life emotional situations. For example, in one study they compared emotional expressions of professional tennis players winning or losing a point.

They consider these pictures ideal because the stakes in such games are extremely high from an economic and prestige perspective.

Expressions numbered 1,4,6 show tennis player's face on losing a point; expressions numbered 2,3,5 show a player after winning a point). Tests show that those looking at facial expressions alone cannot determine what the true emotion is. Credit: Reuters: Used with permission from Hebrew University of Jerusalem

To pinpoint how people recognize such images, Dr. Hillel Aviezer of the Hebrew University, Dr. Yaacov Trope of New York University and Dr. Alexander Todorov of Princeton showed different versions of the pictures to three groups of participants: 1) the full picture with the face and body; 2) the body with the face removed; and 3) the face with the body removed.

The participants could easily tell apart the losers from winners when they rated the full picture or the body alone, but they were at chance level when rating the face alone. Yet they were convinced that it was the face that revealed the emotional impact, not the body. The authors named this effect "illusory valence," reflecting the fact that participants said they saw clear valence (that is, either positive or negative emotion) in what was objectively a non-diagnostic face.

In an additional study, they asked viewers to examine a more broad range of real-life intense faces. These included intense positive situations, such as joy (seeing one's house after a lavish makeover), pleasure (experiencing an orgasm), and victory (winning a critical tennis point), as well as negative situations, such as grief (reacting at a funeral), pain (undergoing a nipple/naval piercing), and defeat (losing a critical tennis point).

Again, viewers were unable to tell apart the faces occurring in positive vs. negative situations. To further demonstrate how ambiguous these intense faces are, the researchers "planted" faces on bodies expressing positive or negative emotion. Sure enough, the emotional valence of the same face on different bodies was determined by the body, flipping from positive to negative depending on the body with which they appeared.

"These results show that when emotions become extremely intense, the difference between positive and negative facial expression blurs," says Aviezer. "The findings, challenge classic behavioral models in neuroscience, social psychology and economics, in which the distinct poles of positive and negative valence do not converge.

"From a practical-clinical perspective, the results may help researchers understand how body/face expressions interact during emotional situations. For example, individuals with autism may fail to recognize facial expressions, but perhaps if trained to process important body cues, their performance may significantly improve."

Published in Science.

Comments