Science mysteries are meant to be solved and so researchers have reported the first detailed data on methane-exhaling microbes that live deep in the hydrothermal vents of hot undersea volcanoes. Just as biologists studied the habitats and life requirements of giraffes and penguins when they were new to science, says microbiologist James Holden of the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, "for the first time we're studying these subsurface microorganisms, defining their habitat requirements and determining how they differ among species."

Because the study involves methanogens - microbes that inhale hydrogen and carbon dioxide to produce methane as waste - it may also shed light on natural gas formation on Earth. One major goal was to test results of predictive computer models and to establish the first environmental hydrogen threshold for hyperthermophilic (super-heat-loving), methanogenic (methane-producing) microbes in hydrothermal vent fluids.

In a two-liter bioreactor where the scientists could control hydrogen levels, they grew pure cultures of hyperthermophilic methanogens from their study site alongside a commercially available hyperthermophilic methanogen species. he researchers found that growth measurements for the organisms were about the same. All grew at the same rate when given equal amounts of hydrogen and had the same minimum growth requirements. Holden and Helene Ver Eecke at UMass Amherst used culturing techniques to look for organisms in nature and then study their growth in the lab. Co-investigators Julie Huber at the Marine Biological Laboratory on Cape Cod provided molecular analyses of the microbes, while David Butterfield and Marvin Lilley at the University of Washington contributed geochemical fluid analyses.

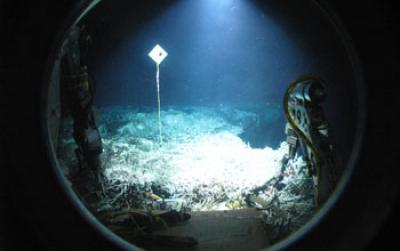

A hydrothermal vent field at Axial Volcano seen through the porthole of the submersible Alvin. Credit: Mark Spear/WHOI

Using the research submarine Alvin, they collected samples of hydrothermal fluids flowing from black smokers up to 350 degrees C (662 degrees F), and from ocean floor cracks with lower temperatures.

Research submarine Alvin extends its mechanical arm to a high-temperature black smoker at Endeavor Segment. Credit: Bruce Strickrott/WHOI

Samples were taken from Axial Volcano and the Endeavour Segment, both long-term observatory sites along an undersea mountain range about 200 miles off the coast of Washington and Oregon and more than a mile below the ocean's surface.

"We used specialized sampling instruments to measure both the chemical and microbial composition of hydrothermal fluids," says Butterfield. "This was an effort to understand the biological and chemical factors that determine microbial community structure and growth rates."

A happy twist awaited the researchers as they pieced together a picture of how the methanogens live and work. At the low-hydrogen Endeavour site, they found that a few hyperthermophilic methanogens eke out a living by feeding on the hydrogen waste produced by other hyperthermophiles.

"This was extremely exciting," says Holden. "We've described a methanogen ecosystem that includes a symbiotic relationship between microbes."

The project also puts us on the path to answering questions such as what metabolic processes may have looked like on Earth three billion years ago, and what alien microbial life might look like on other planets.

Comments