The interactions between sound and light in this optomechanical crysta can result in mechanical vibrations with frequencies as high as tens of gigahertz, or 10 billion cycles per second. Being able to achieve such frequencies gives these devices the ability to send large amounts of information, and opens up a wide array of potential applications—everything from lightwave communication systems to biosensors capable of detecting (or weighing) a single macromolecule.

It could also, Painter says, be used as a research tool by scientists studying nanomechanics. "These structures would give a mass sensitivity that would rival conventional nanoelectromechanical systems because light in these structures is more sensitive to motion than a conventional electrical system is."

And all of it on a silicon microchip.

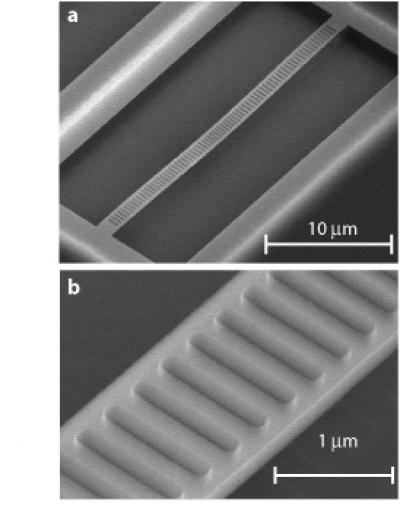

Scanning electron micrograph of the optomechanical crystal. (At bottom) This is a closer view of the device's nanobeam. Credit: M. Eichenfield, et. al., Nature, Advanced Online Publication (Oct. 18, 2009)

Optomechanical crystals focus on the most basic units (quanta) of light and sound; photons and phonons, respectively. There has been considerable research into both photonic and phononic crystals, which use tiny energy traps called bandgaps to capture quanta of light or sound within their structures. What hadn't been done before was to put those two types of crystals together and see what they are capable of doing. That is what the Caltech team has done.

"We now have the ability to manipulate sound and light in the same nanoplatform, and are able to interconvert energy between the two systems," says Oskar Painter, associate professor of applied physics at Caltech and principal investigator on the paper describing the work. "And we can engineer these in nearly limitless ways."

The volume in which the light and sound are simultaneously confined is more than 100,000 times smaller than that of a human cell, notes Caltech graduate student Matt Eichenfield, the paper's first author. "This does two things," he says. "First, the interactions of the light and sound get stronger as the volume to which they are confined decreases. Second, the amount of mass that has to move to create the sound wave gets smaller as the volume decreases. We made the volume in which the light and sound live so small that the mass that vibrates to make the sound is about ten times less than a trillionth of a gram."

Eichenfield points out that, in addition to measuring high-frequency sound waves, the team demonstrated that it's actually possible to produce these waves using only light. "We can now convert light waves into microwave-frequency sound waves on the surface of a silicon microchip," he says.

These sound waves, he adds, are analogous to the light waves of a laser. "The way we have designed the system makes it possible to use these sound waves by routing them around on the chip, and making them interact with other on-chip systems. And, of course, we can then detect all these interactions again by using the light. Essentially, optomechanical crystals provide a whole new on-chip architecture in which light can generate, interact with, and detect high-frequency sound waves."

These optomechanical crystals were created as an offshoot of previous work done by Painter and colleagues on a nanoscale "zipper cavity," in which the mechanical properties of light and its interactions with motion were strengthened and enhanced.

Like the zipper cavity, optomechanical crystals trap light; the difference is that the crystals trap—and intensify—sound waves, as well. Similarly, while the zipper cavities worked by funneling the light into the gap between two nanobeams—allowing the researchers to detect the beams' motion relative to one another—optomechanical crystals work on an even tinier scale, trapping both light and sound within a single nanobeam.

"Here we can actually see very small vibrations of sound trapped well inside a single 'string,' using the light trapped inside that string," says Eichenfield. "Importantly, although the method of sensing the motion is very different, we didn't lose the exquisite sensitivity to motion that the zipper had. We were able to keep the sensitivity to motion high while making another huge leap down in mass."

"As a technology, optomechanical crystals provide a platform on which to create planar circuits of sound and light," says Kerry Vahala, the Ted and Ginger Jenkins Professor of Information Science and Technology and professor of applied physics, and coauthor on the paper. "These circuits can include an array of functions for generation, detection, and control. Moreover," he says, "optomechanical crystal structures are fabricated using materials and tools that are similar to those found in the semiconductor and photonics industries. Collectively, this means that phonons have joined photons and electrons as possible ways to manipulate and process information on a chip."

And these information-processing possibilities are well within reach, notes Painter. "It's not one plus one equals two, but one plus one equals ten in terms of what you can do with these things. All of these applications are much closer than they were before."

Published in Nature.

Comments