A University of Texas at Arlington team exploring pigeons as a model for vertebrate evolution has uncovered that mutations and interactions among just three genes create a wide variety of color variations. One of those genes, they also found, may be an example of a "slippery gene" more prone to evolutionary changes.

John W. "Trey" Fondon, an assistant professor of biology, is co-author of a study that begins to unravel the molecular basis for the color palette of domestic pigeons breeds known as "fancy pigeons." Due mostly to organized breeding in Europe and Asia, there are hundreds of types of pigeons that have evolved to include numerous color variations on the blue/black model, including shades of gray, red, and brown.

The genes in the study have previously been linked to skin and hair color

variation

among people, as well as the development of melanoma.

"The pigeon really has been neglected as a model system, and we are changing that," Fondon said, adding that such studies can help in an overall understand of vertebrate systems. "The things that shape diversity also shape disease."

The results are being published online Feb. 6 in the journal Current Biology. Eric T. Domyan, a post-doctoral fellow in the lab of University of Utah professor Michael D. Shapiro, is lead author.

Other co-authors include Shapiro; Shreyas Krishnan and Clifford Rodgers, of UT Arlington; Zev Kronenberg, Michael W. Guernsey, Anna Vickery and Mark Yandell, of University of Utah; Raymond E. Boissy, of the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine; and Pamela Cassidy and Sancy A. Leachman, of the Oregon Health & Science University.

Shapiro's team at University of Utah published research last year in the journal Science that revealed results from the first large-scale sequencing of the pigeon genome. That collection of DNA from 40 pigeons, provided the basis for the new work.

Geneticists like Fondon have turned to dog breeds in the past to understand the molecular basis of phenotype changes because dog breeds are so varied. Fondon said scientists hoping to understand more about how characteristics vary can find even greater statistical power and diversity in studying domestic pigeons.

Fondon's laboratory worked in parallel with researchers at Utah to find that coding and regulatory variations in the interactions among the genes Tyrp1, Sox10 and Slc45a2 control multiple color phenotypes, or appearances, in pigeons. For example, researchers found that the ash-red mutation in Tyrp1, a gene that plays a large role in color determination, arose just once and was spread throughout the species by selective breeding.

They also found that some color changes evolved through changes in the same gene that happened at different times – hinting at the existence of a "slippery gene."

Fondon's team found two independent deletions of regulatory sequences near the Sox10 gene produce "recessive red" pigmentation. These mutations happened at different points in evolution, and researchers believe it is no coincidence they hit the same spot, as this same region is also deleted in color mutants of chickens and mice, Fondon said. There are indications of yet more independent mutations of this "hotspot."

More research is needed, but Fondon expects significant progress in understanding is on the horizon.

"These traits are falling like dominoes in terms of our understanding their genetic origins. It took hundreds of years to set them up and now they are just falling," Fondon said.

The name of the new paper is "Epistatic and combinatorial effects of pigmentary gene mutations in the domestic pigeon."

"Dr. Fondon is contributing important, essential discoveries to our understanding of how genes change over time. His work is strengthening our already vibrant Genome Biology Group and the College of Science overall," said Pamela Jansma, dean of the UT Arlington College of Science.

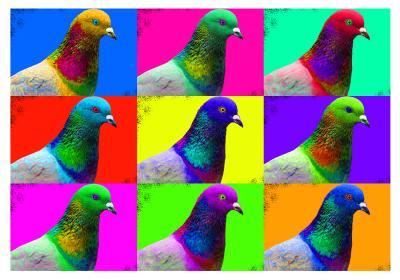

Pigeons aren't quite this colorful, but there are a wide variety of appearances. Geneticists looking at the genes that underlie color combinations have published their work in Current Biology.

(Photo Credit: John W. Fondon, UT Arlington)

Comments