Skin cancer is a common and growing problem, accounting for one in every three cancers diagnosed worldwide, according to the World Health Organization. Recent findings suggest that malignant melanoma, the most dangerous form of skin cancer, is has grown dramatically in the last few decades.

Eczema is a blanket term for medical conditions that cause the skin to become inflamed. It affects about 10% to 20% of infants and about 3% of adults and children in the U.S. Most infants who develop the condition outgrow it at a young age.

There is ongoing debate surrounding allergic diseases and their impact on the likelihood of developing cancer, with some studies suggesting that eczema is associated with a reduced risk of skin cancer. However, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions based on studies of human populations because eczema symptoms vary in severity and drugs used to treat the condition might also influence cancer. The new paper is the first to show that allergy caused by the skin defects could actually protect against skin cancer.

A new study finds that the immune response triggered by eczema could help prevent tumor formation, by shedding potentially cancerous cells from the skin. Eczema can result from the loss of structural proteins in the outermost layers of the skin, leading to a defective skin barrier. Genetically engineered mice lacking three skin barrier proteins ('knock-out' mice) were used in the King's study to replicate some of the skin defects found in eczema sufferers.

The researchers compared the effects of two cancer-causing chemicals in normal mice and mice with the barrier defect (the knock-out mice). The number of benign tumours per mouse was six times lower in knock-out mice than in normal mice. The findings suggest that defects in the epidermal barrier protected the genetically engineered mice against benign tumour formation.

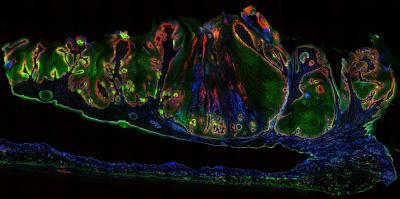

Cross-section of mouse skin tumor. Credit: King's College London

Researchers found that both types of mice were equally susceptible to acquiring cancer-causing mutations. However, an exaggerated inflammatory reaction in knock-out mice led to enhanced shedding of potentially cancerous cells from the skin. This cancer-protective mechanism bears similarities to that which protects skin from environmental assaults such as bacteria.

Professor Fiona Watt, Director of the Centre for Stem Cells and Regenerative Medicine, said: 'We are excited by our findings as they establish a clear link between cancer susceptibility and an allergic skin condition in our experimental model. They also support the view that modifying the body's immune system is an important strategy in treating cancer.

'I hope our study provides some small consolation to eczema sufferers – that this uncomfortable skin condition may actually be beneficial in some circumstances.'

Dr Mike Turner, Head of Infection and Immunobiology at the Wellcome Trust, said: 'Skin cancer is on the rise in many countries and any insight into the body's ability to prevent tumour formation is valuable in the fight against this form of cancer. These findings that eczema can protect individuals from skin cancer support theories linking allergies to cancer prevention and open up new avenues for exploration whilst providing some (small) comfort for those suffering from eczema.'

Source: King's College London

Comments