Eighteen-year-old Sören Wolf was born with only one hand but when it comes to a prosthetic second one, he's enthusiastic about both the “i-LIMB” and the ”Fluidhand.”

The new “i-LIMB” prosthetic hand developed and distributed by Scottish company “Touch Bionics” has distinct advantages over similar competitive models. Complex electronics and five motors contained in the fingers enable every digit of the i-LIMB to be powered individually. A passive positioning of the thumb enables various grip configurations to be activated. The myoelectric signals from the stump control the prosthetic hand; muscle signals are picked up by electrodes on the skin and transferred to the control electronics in the prosthetic hand.

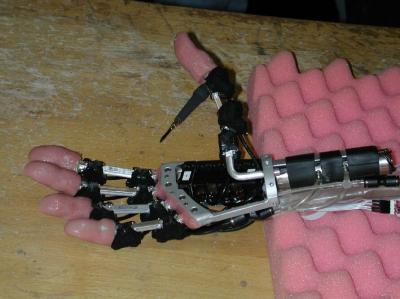

The “Fluidhand” from Karlsruhe, thus far developed only as a prototype that is also being tested in the Orthopedic University Hospital in Heidelberg, is based on a somewhat different principle. Unlike others, the new hand can close around objects, even those with irregular surfaces. A large contact surface and soft, passive form elements greatly reduce the gripping power required to hold onto such an object. The hand also feels softer, more elastic, and more natural than conventional hard prosthetic devices.

The flexible drives are located directly in the movable finger joints and operate on the biological principle of the spider leg – to flex the joints, elastic chambers are pumped up by miniature hydraulics. In this way, index finger, middle finger and thumb can be moved independently. The prosthetic hand gives the stump feedback, enabling the amputee to sense the strength of the grip.

Thus far, Sören has been the only patient in Heidelberg who has tested both models.

“This experience is very important for us,” says Simon Steffen, Director of the Department of Upper Extremities at the Orthopedic University Hospital in Heidelberg.

The two new models were the best of those tested, with a slight advantage for Fluidhand because of its better finishing, the programmed grip configurations, power feedback, and the more easily adjustable controls. However, this prosthetic device is not in serial production.

“First the developers have to find a company to produce it,” says Alfons Fuchs, Director of Orthopedics Engineering at the Orthopedic University Hospital in Heidelberg, as the costs of manufacturing it are comparatively high. However it is possible to produce an individual model.

Thus far, only one patient in the world has received a Fluidhand for everyday use. A second patient will soon be fitted with this innovative prosthesis in Heidelberg.

Comments