In the old days, when reporters were common in newsrooms, they were less likely to begin, whereas in modern times when editors instead hire journalists to appeal to advertisers selling products to clear demographics, they are easier to launch. What really gets bizarre claims like that PFAS in water is killing people going, though, is modern technology. This week we have claims by Democrats that Republicans staged the attempted assassination of former President Donald Trump - and the Democratic donor was actually a long-term operative of Blackrock groomed from childhood. And that mainstream media isn't being allowed to disclose it.

That is why modern technology is also considered part of the conspiracy.

A new paper hopes to examine the extent, causes and consequences of such beliefs. The basis is a survey, not science, so just like epidemiology cannot be used to make important decisions, there's no reason to think Amazon Echo, Google Search, or any Contact Tracing is anything other than what they are designed to be; ways to sell you products.

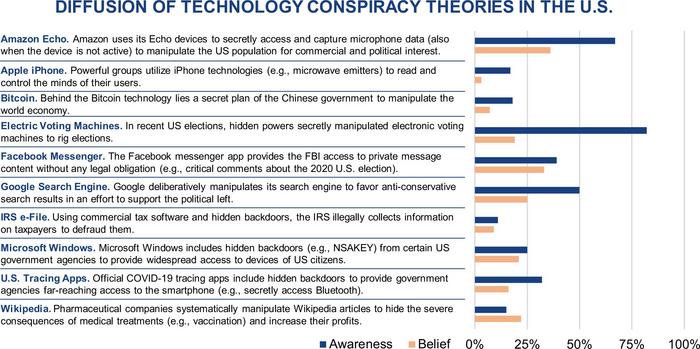

Based on 1,007 US participants representative of the general population. Credit: Information Systems Research. Copyright © 2024 The Author(s): https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2022.0494, used under a Creative Commons Attribution License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0

Usage Restrictions

They found that conspiracies were common. People tend to suspend disbelief when claims match their existing bias. For example, 67% of respondents have heard of and 36% agreed with the notion that Amazon Echo smart speakers eavesdrop on users even when the device is turned off, in order to manipulate the population.

For six out of ten different conspiracy theories relating to technology, at least 20% of the participants knew about the theory; and for five out of ten of these theories, at least 20% believed in them.

The researchers then built on data from a field study and three experiments. In the field study, the research team analyzed the formation of technology conspiracy beliefs associated with the coronavirus tracing app in Germany. An experiment on a newly introduced smart car assistant technology yielded additional insights into how not only the technology, but also the issuer of the technology, can give rise to technology conspiracy beliefs.

In addition to the prevalence and emergence of these beliefs, the researchers found evidence that technology conspiracy beliefs have detrimental consequences beyond the technology itself. The data indicate that the endorsement of technology conspiracy beliefs can set a vicious cycle in motion in which individuals develop a harmful “conspiracy mindset”, increasingly interpreting their environment through the lens of conspiracy theories.

This enabled the researchers to provide an initial understanding of which technologies and what kinds make them more likely to become the focus of conspiracy beliefs. What can that mean for policy? Not much. Plumbers say 'water finds a way' while biologists say 'nature finds a way' and in culture, conspiracies can never be stopped, largely because they contain enough truth to be plausible if you accept a daisy-chain of circumstantial claims beyond reality.

“The mindset fostered by such beliefs is associated with a breakdown of social collaboration and constructive political debate, which would affect society’s ability to respond to future crises,” says Manuel Trenz, Professor for Interorganizational Information Systems, University of Göttingen.

Comments