Sulfur left over from refining fossil fuels can be transformed into cheap, lightweight, plastic lenses for infrared devices, including night-vision goggles, a University of Arizona-led international team has found.

The team successfully took thermal images of a person through a piece of the new plastic. By contrast, taking a picture taken through the plastic often used for ordinary lenses does not show a person's body heat.

"We have for the first time a polymer material that can be used for quality thermal imaging – and that's a big deal," said senior co-author Jeffrey Pyun, whose lab at the UA developed the plastic. "The industry has wanted this for decades."

These lenses and their next-generation prototypes could be used for anything involving heat detection and infrared light, such as handheld cameras for home energy audits, night-vision goggles, perimeter surveillance systems and other remote-sensing applications, said senior co-author Robert A. Norwood, a UA professor of optical sciences.

The lenses also could be used within detectors that sense gases such as carbon dioxide, he said. Some smart building technology already uses carbon dioxide detectors to adjust heating and cooling levels based on the number of occupants.

In contrast to the materials currently used in infrared technology, the new plastic is inexpensive, lightweight and can be easily molded into a variety of shapes, said Pyun, associate professor of chemistry and biochemistry at the UA.

A University of Arizona-led research team has discovered a simple process for making a new lightweight plastic from the inexpensive and abundant element sulfur. This plastic can be molded into easy-to-make, lightweight lenses that transmit infra-red light.

(Photo Credit: Jared Griebel/ Pyun lab, University of Arizona department of chemistry and biochemistry.)

The researchers have filed an international patent for their new chemical process and its application for lenses. Several companies have expressed interest in the technology, he said.

Norwood and his colleagues in the UA College of Optical Sciences tested the optical properties of the new lens materials and found they are transparent to mid-range infrared and result in lenses with high optical focusing power.

The team's discovery could provide a new use for the sulfur left over when oil and natural gas are refined into cleaner-burning fuels. Although there are some industrial uses for sulfur, the amount generated from refining fossil fuels far outstrips the current need for the element.

The international team's research article, "New infrared transmitting material via inverse vulcanization of elemental sulfur to prepare high refractive index polymers," is published online in the journal Advanced Materials.

Pyun and Norwood's co-authors are Jared J. Griebel, Dominic H. Moronta, Woo Jin Chung, Adam G. Simmonds, Richard S. Glass, Soha Namnabat, Roland Himmelhuber, Kyung-Jo Kim, John van der Laan and Eustace L. Dereniak of the UA; Eui Tae Kim and Kookheon Charof Seoul National University in Korea; and Ngoc Nguyen and Michael E. Mackay of the University of Delaware.

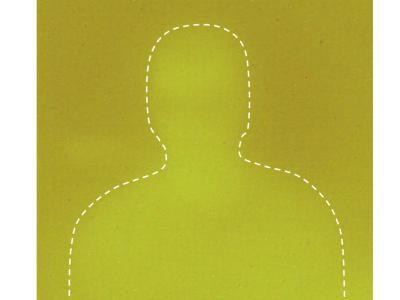

A thermal image of University of Arizona researcher Jared Griebel taken through ordinary plastic with an infrared camera. The ordinary plastic transmits very little infrared light. Courtesy of Eustace L. Dereniak, University of Arizona College of Optical Sciences.

(Photo Credit: Courtesy of Eustace L. Dereniak, University of Arizona College of Optical Sciences.)

Research funding was provided by the American Chemical SocietyPetroleum Research Foundation, the U.S. National Science Foundation, the National Research Foundation of Korea, the Korean Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, the State of Arizona Technology Research Initiative Fund and the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research.

Norwood said the new plastic is transparent to wavelengths of light in the mid-infrared range of 3 to 5 microns – a range with many uses in the aerospace and defense industries.

The new lenses also have a high optical, or focusing, power – meaning they do not need to be very thick to focus on nearby objects, making them lightweight.

Depending on the amount of sulfur in the plastic, the lenses have a refractive index between 1.865 to 1.745. Most other polymers that have been developed have refractive indices below 1.6 and transmit much less light in the mid-range infrared, the authors wrote in their paper.

Pyun and colleagues reported their creation of the new plastic and its possible use in lithium-sulfur batteries in 2013. The researchers have filed patents for that technology as well and several companies are interested.

Pyun and first author Griebel, a UA doctoral candidate in chemistry and biochemistry, were trying to transform liquid sulfur into a useful plastic that could be produced easily on an industrial scale.

The chemists dubbed their process "inverse vulcanization" because it requires mostly sulfur with a small amount of an additive. Vulcanization is the chemical process that makes rubber more durable by adding a small amount of sulfur to rubber.

To make lenses, Griebel poured the liquid concoction into a silicone mold similar to those used for baking cupcakes.

"You can pop the lenses out of the mold once it's cooled," he said. "Making lenses with this process – it's two materials and heat. Processing couldn't be simpler, really."

The team's next step is comparing properties of the new plastic with existing plastics and exploring other practical applications such as optical fibers.

A thermal image of University of Arizona researcher Jared Griebel taken through a piece of new sulfur-based plastic using an infrared camera. Courtesy of Eustace L. Dereniak, University of Arizona College of Optical Sciences.

(Photo Credit: Courtesy of Eustace L. Dereniak, University of Arizona College of Optical Sciences.)

Comments