Instead, humans rely on several regions of the brain, each designed to accomplish different primitive tasks, in order to make sense of a sentence, the study suggests. Depending on the type of grammar used, the brain will activate a certain set of regions to process it.

"We're using and adapting the machinery we already have in our brains," said study coauthor Aaron Newman, from the University of Rochester. "Obviously we're doing something different [from other animals], because we're able to learn language unlike any other species. But it's not because some little black box evolved specially in our brain that does only language, and nothing else."

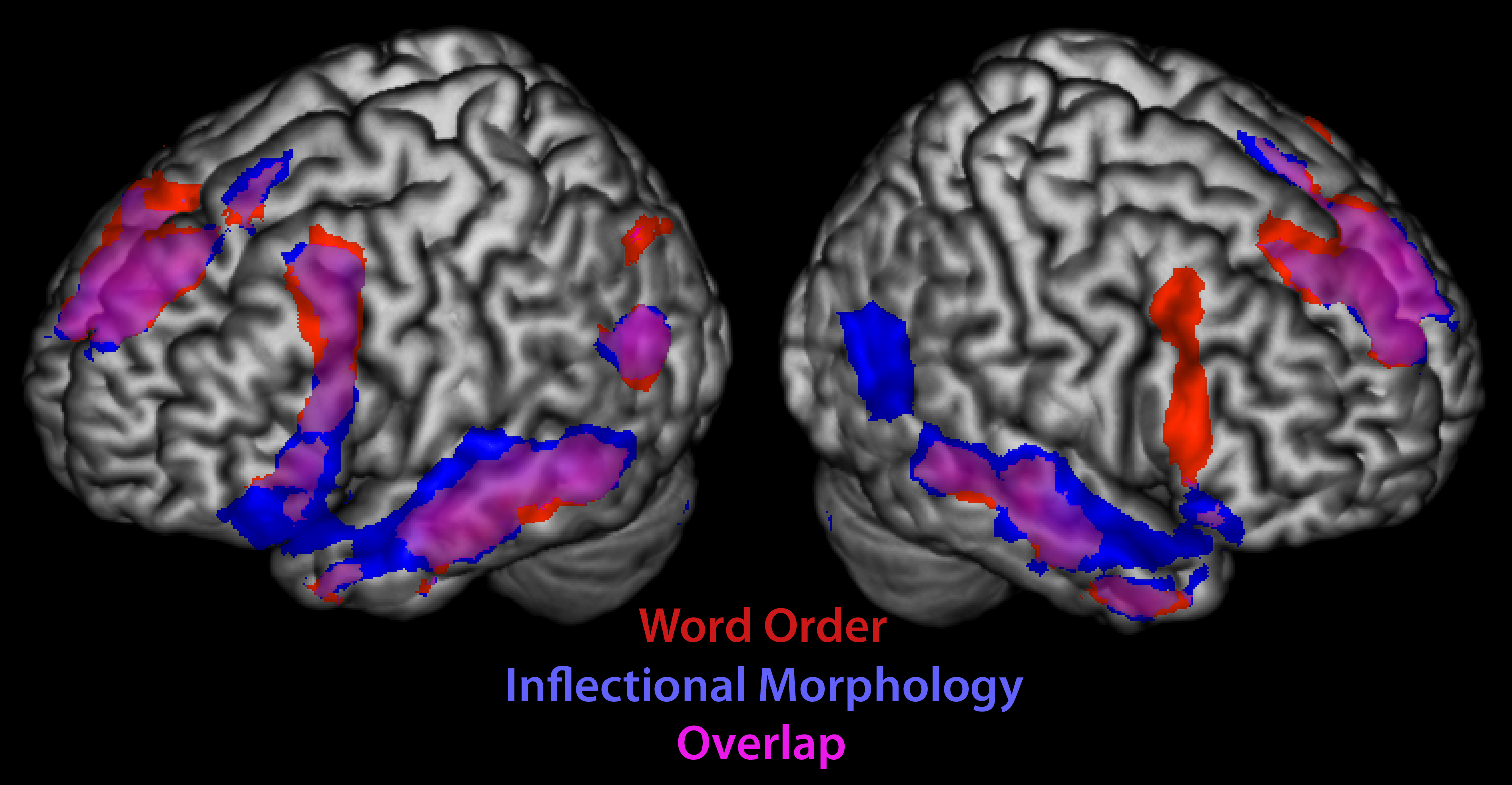

(Photo credit: University of Rochester)

The findings could eventually find applications in medicine, for example, helping speech therapists teach language to a person with brain damage in certain areas but not others, such as a stroke victim.

To determine whether different brain regions were used to decipher sentences with different types of grammar, the scientists turned to American Sign Language, because it does not rely on the order of words to convey the relationships between sentence elements.

When an English speaker hears the sentence "Sally greets Bob," it's clear from the word order that Sally is the subject doing the greeting and Bob is the object being greeted, not vice versa.

Other languages (Spanish, for example) rely on inflections, such as suffixes tacked on to the ends of words, to convey subject-object relationships, and the word order can be interchangeable.

American Sign Language has the helpful characteristic that subject-object relationships can be expressed in either of the two ways – using word order or inflection. Either a signer can sign the word "Sally" followed by the words "greets" and "Bob", or the signer can use physical inflections such as moving hands through space or signing on one side of the body to convey the relationship between elements.

For the study, the team formed 24 sentences and expressed each of those sentences using both methods. Videos of the sentences being signed were then played for the subjects of the experiment, native signers who were lying on their backs in MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) machines with coils around their heads to monitor which areas of the brain were activated when processing the different types of sentences.

Researchers found that distinct regions of the brain that are used to process the two types of sentences: those in which word order determined the relationships between the sentence elements, and those in which inflection was providing the information.

In trying to understand different types of grammar, humans draw on regions of the brain that are designed to accomplish primitive tasks that relate to the type of sentence they are trying to interpret. For instance, a word order sentence draws on parts of the frontal cortex that give humans the ability to put information into sequences, while an inflectional sentence draws on parts of the temporal lobe that specialize in dividing information into its constituent parts.

"These results show that people really ought to think of language and the brain in a different way, in terms of how the brain capitalizes on some perhaps preexisting computational structures to interpret language," Newport said.

Citation: Newman et al., 'Dissociating neural subsystems for grammar by contrasting word order and inflection', Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2010, 107(16): 7539; doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003174107

Comments