How are blogs changing the way science news develops and is reported?

The commissioning of the Large Hadron Collider at CERN will offer a

telling case study over the next few years. Who will be first with news

of the fabled Higgs Boson, and how will we know if they're right?

I already gave you here a general report of the conference, and the session above. However today it was nice for me to hear again my talk, and since I still stand by what I said there, I decided to make a transcript for the hearing-impaired among you who would not listen to the recording. It is offered to you below.

Tommaso Dorigo, Communicating Discoveries in the Blog Era

WCSJ 2009, Westminster Central Hall, London July 2nd

WCSJ 2009, Westminster Central Hall, London July 2nd

So, I'm very happy to be here. This for me is a slightly unusual venue, since I am used to science conferences: this is nice for a change. I am going to try and tell you how we will learn about the Higgs boson: where the first real news will come from. But the focus of my presentation is about how we, scientists, try to communicate news to the public and how this can be improved, because I think it needs to be improved.

So, there is a gap between scientists -at least I feel this in physics, which is my area of expertise-, and the public. There is a gap because scientists publish in scientific magazines which are peer-reviewed, they are very dry, you cannot pick up one and read it if you do not have a background, while there has to be a means of distributing that information. This fact that scientists have to publish in peer-reviewed magazines and not in magazines that can actually reach more people is a problem.

Then there is the competition among experimental groups, which forces them to actually be very uptight and not let things leak out from their collaborations before they are ready to publish. And this cuts out the discussion, and makes things less controversial but also drier; less communication is bad.

So there is an absence of culture of Science in newspapers and we know about that, and we fight that. We have to face it, one can happily live without knowing Particle Physics. This is not true about other fields of Science, but it might look like a lost cause to try and let everybody know why the LHC is important, why we spent so much money building it, what is the business with this Higgs boson thing. And Physics has the problem that it is considered too hard, so people want to read about Medicine because it impacts their life, but not so much about Particle Physics.

You know about the general crisis of printed matter and the internet. This does not worsen the situation about feeling this gap that exists, but the problem for Science magazines is that they only reach out people who actively look for that information. This from my point of view, the point of view of trying to get more people involved. And then there is a problem, one problem that we can solve, is that the general users do not always want to know everything about everything, but they want to focus on a narrow subset of things, and they want to have constant updates on those things, rather than reading about it every couple of months about the Higgs boson in general Science magazines. So I think this latter issue may be addressed by blogs.

There has been an onset of serious blogging activities in Physics. Not many people do it, because people do not have so much time in their hands, I mean, I am a scientist, I do this from 9 to 10PM in the evening, right, but I have realized that part of my job is try to communicate why what I do is important. I feel it as a duty to try and do that. So devoting some part of your time on this is important. So, it is up to us, to scientists, to try and convince the public about the importance of basic research.

As I said, blogs can do something that scientific popularization magazines do not do, that is focus on something very particular, but have an update every two or three days. So this is what you find in blogs that you cannot find in scientific magazines. Ok, you can find that on the web sites of those magazines, but that is still discontinuous.

Also the communication flow between scientific collaborations and scientific magazines is imperfect, because, as Matthew was saying before, reporters pick up stories from the web, and sometimes they pick up good ones, and sometimes they don't. He was blaming the physicists that were blogging about the string wars thing, by saying that this is not the real big news, but the problem is that they picked it up. So, people talk about things in the web, and it is up to reporters, I think, to decide what is worth and what is not.

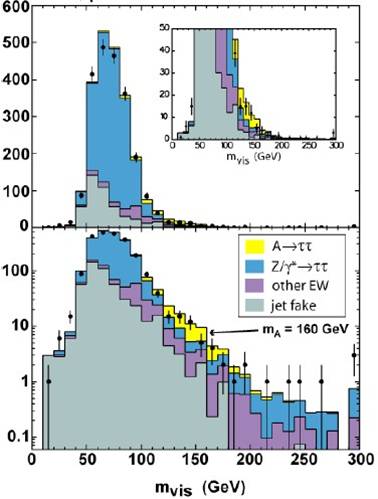

In this case [the picture shown above] you see a signal published by the CDF collaboration, it was a small excess of data which might be indicative of a bump in this mass spectrum, a new particle maybe. This was a two-sigma statistical fluctuation, something that appears every day: we know about this: these things happen, so it was not so extraordinary to us, but it got media attention because I reported about it in my blog, I discussed about it in another blog, and we made up things, "what if this is it, then we might be looking it in another sample", and blah, and I got interviewed by New Scientist, and then some incorrect information leaked out, and then the Economist picked it up, and there followed some media hype about this thing, but it was based on a very non-news, if you like.

This actually was detrimental, because the CDF collaboration -which is the collaboration I am working for, and which produced this result-, resented the fact that they were not in the loop, because they were cut out, since Science reporters could actually address the issue by talking to bloggers which are also in the collaboration and knew about this, so that was a problem for the collaborations.

The problem is that we are scaling up things, now the LHC will have collaboations that hare three to four times lartger than those at the Tevatron at Fermilab, which is the one I was talking about, and so there are steps which are being taken to prevent these thousands of people to talk about internal business of their collaboration, which want to keep the secrecy, be responsible for what they broadcast, be the ones that broadcast, they do not want to get things misreported, and they want to keep the credit for themselves of course. But hampering blogging activities is not, I think, a step in the right direction.

I will make an example where the damage came not from blogs, but came from scientists who like to talk, and like to put reserved material in their public web pages to distribute it to colleagues. So, we like to talk, and what can you do to stop 5000 physicists from talking to the other what, the other 10,000 in the world ? Bloggers put their faces in their pages, so they are the ones that actually can be blamed if they do something incorrectly, but acually the problem comes from elsewhere.

So who will have the news about the higgs boson, which is this handsome particle which was hypothesized more than 40 years ago, which fixes everything -well, not everything but many things about the subatomic world ? I think it will be announced many times. This has already started happening. It started in 2001 at CERN, and then it is going on, as I said, the bump you saw, it was a bump from the Higgs boson , a particular kind, but still a Higgs boson.

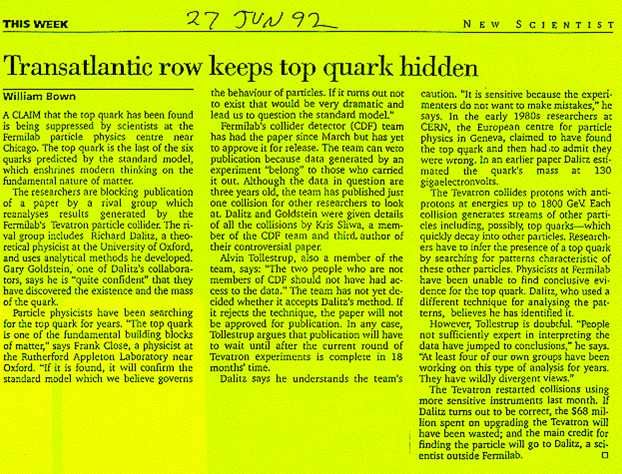

A similar situation happened with the top quark, which is the last important particle of the Standard Model which was discovered by my experiment in 1994, this particle was actually "discovered" by Rubbia in the eighties and then retracted. And then, in 1992 my experiment saw one event, on which some collaborators fantasized, they picked it up and they made a paper outside of the collaboration. There followed a controversy, they were expelled. This [see paper clipping below] is New Scientist again, discussing this thing, what, 17 years ago.

So what the problem is, is that before a potential signal is proven correct, it takes weeks, or even months, for the collaboration to check and make sure everything is correct. We have a very very long process before we can actually say and publish something. We have status reports, preblessings, internal reviewing, blessings; even the last graduate student can break an analysis by making a pointed comment. And then you have a draft that goes through review, and only after this review can you publish.

Scientific collaborations are bound to make correct claims, so this slows them down. Whether the announcement of a new particle comes from a scientific collaboration or whether it comes from a blog or from an anonymous comment depends on how much they are quick in distributing these news. One way out of this would be for scientific collaborations to get their own approved blogs, but they would have to be agile and quick. I do not see this happening because they have a problem with alerting their competition, if they are on to something. You know, there is competition in the scientific world, we have to get funded and... So, fortunately we have the luxury of having more than a single experiment doing some particular physics. It may damage their reputation if they put out stuff that they have to retract. We saw it with Rubbia, but it did not do much damage to him, apparently.

So is it going to be blogs ? Bloggers are tightly watched. I am tightly watched. Anonymous blogs, on the other hand, or anonymous comments in other people's blogs, might be the way, are the place to look for the first real news. But anonymous blogs, nobody reads them. If they are not so anonymous people read them, but then, ok... And anonymous comments in visible blogs, that is more probable, because, this will be the way in my opinion that things will turn out, and I have an example of this.

I will make a couple of example of how things work. In June 2007 we had another supersymmetric Higgs boson signal by the competing experiment at the Tevatron, DZERO, coming out, but it came out from an anonymouys comment in my blog. Somebody said: "Well, have you heard about this, you are not in DZERO but do you know about it", "is it going ot come out, it seems significant", blah. I of course picked the story up, and it got media attention immediately.

I spoke with Dennis Overbye over the phone several times on this, and it got on the New York Times, got elsewhere. Of course a bubble that later blew up. It was not a signal, it was something that the DZERO collaboration did not want to come out, because they were not sure yet about it , and it was not good to publish it in fact. I did not publish, I just talked about a rumour. It was a rumour, but the DZERO collaboration was not happy at all, I think. They had their reasons, but it was not my fault, it was the fault of reporters that pick up stories, and sometimes they build stories about nothing.

So this is my point. I avoided Fermilab for a while, because they could scratch my car, but the mesasge to get out is that this showed the weakness of the system. Somebody anonymously, some scientist who does not want to appear, gets the news out.

The other example I am going to make is the one about "anomalous muons" from the CDF collaboration last year at around Halloween time. It appeared that they had something potentially groundbreaking, they had requested earlier a very very strict control, even much stricter: if you were a member of CDF you could not access the draft unless you asked for it to the spokespersons. Despite this, I was mentioned as the weak link, they were concerned that my blog could broadcast this thing, but it was not in my blog that it leaked out. In fact, it transpired that some of my CDF colleagues had put the reserved material in their public web pages just to distribute it to their fellow theorists around the world, and by googling something, if you were smart enough you could find it. There is a lesson here to take: if you want to get some news, you put on an automatic google search and it will work wondrs for you, you just scan the web sites of scientists.

So there are concerns about blogging and distributing information which might prove to not be the real thing. Rumours. The "media fatigue" thing. I mean, people are concerned that by talking about the Higgs boson people get fed up. I take a scientific stand on this. If you know what detailed balancing is, you have a two state system. You have Readers and non-Readers. Readers are a tiny minority. You are concerned about losing a small percentage of your tiny minority, when there is a billion people that you could reach. Even if you lose somebody at the high rate here, you gain by having even a small rate of people getting to read stuff.

Imagine a model where the Higgs boson is not talked about, occasionally people talk about it, you get to read it in magazines, but until the collaboration which is looking for it makes an announcement nobody talks about it. Everybody reads about it at that point, like for the LHC jamboree last year, and then what happens is that one month afterwards, nobody remembers what the Higgs is.

Then compare it to another model. Every two months somebody comes up with rumours. "We have a two sigma signal here". "Oh, and we have a one sigma here, so we might compare things...". And this goes on and on, and its going on actually, and it's continuing. People get to read about the Higgs boson. Reporters have to tell you what the Higgs boson is every time, because they do not have to suppose that you know what it is, but people at the end still remember what the Higgs is when the real discovery appears. So I think that is a point.

Controlling who gets the recognition is the other important point. A discovery announced through an unofficial channel damages the exposure of the experiment and the recognition it gets.

Example 1 is: Tommaso Dorigo sees a bump - this is the way we get to see a new particle, a bump in a mass spectrum- which cannot possibly be a fluctuation in the mass distribution. He owns the data, he can look at the data, he proceeds to broadcast it through his blog, details, plots. He gets expelled by the collaboration at that point, but he gets interviews, media hype, he writes a book, "how I found the Higgs boson while leaving everybody else pants down", and Science magazines thrive, and the experiment at the end has to confirm it, because if it is there in the end they have to write it in a scientific publication. So, this damages the collaboration, ok ?

Example 2 is: Tommaso Dorigo sees a bump, he leakes the information sneaking it in anonymously in the comments thread of somebody else's blog. Nobody gets expelled. I am fine. Nobody gets interviewed or exposure either. But Science reporters this time have nobody to talk about, they have to talk to the collaboration, they do not have somebody to discuss the thing with. The experiment has the time to build a case for a discovery, can choose the timing they need to confirm the claim, and they get the mediatic attention that they deserve.

So I think there is no way to prevent 1, but we have 5000 people in the CERN experiments, so this is not the real issue. It might be an issue, actually, but 2 is more likely to happen. It's not nearly as dangerous, and I think that is the way you will hear about the Higgs boson first.

So, to conclude, blogs are still not so widespread in Physics; there are few people who do it. The problem is that it takes time, and we do not have that much time, but I think it is important to do it. There are collaboration rules that actually prevent me from distributing material to you.

In Physics I see it unlikely that blogs will seriously threaten scientific publications in the near future, but there is this hemorrhage of readers. We need to really work on the detailed balancing thing. Getting more people to read about Science: that is all about a Culture of Science. So It has to be in the schools, it cannot be anywhere else.

Big experiments are going to face tough challenges, and they have to get equipped with their own blogs, and we'll see how well they do. And the Higgs boson will be announced several times before it is actually there, and it might come out from anonymous comments. Thank you.

Comments